I wrote this in 2005, after seeing an excellent exhibit of Diane Arbus’ photography at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. As she is in the news again with another show of her work, the themes of this article seem to me still very relevant.

To say a photograph is worth 1,000 words is to repeat the hoariest of clichés. Does that make the statement completely wrong? Consider that the most unwavering of the Bush II/Cheney administration’s censorship efforts is the suppression of photos. United Statesians are not allowed to see coffins of dead soldiers nor even injured soldiers, not the carnage wrought by their invading military in Iraq, and most certainly not the horrific destruction of Falluja. The corpses of the four mercenaries hung on the Falluja bridge were shown; it was the easiest way to raise a sufficient crescendo of indignation to create the political space needed to carry out the vengeance-inspired massacre that the pitiless logic of invasion required.

By the same logic, the Bush II/Cheney administration and the Pentagon can’t be completely upset by the Abu Ghraib torture photos. Although word of mouth goes a long way when it comes to torture, the handful of leaked photos did demonstrate to people in developing nations around the world just what they can expect should they get in the way of multinational corporations’ asset acquisition programs.

Punishing the enlisted personnel who carried out their orders rather effectively — and what, after all, are enlistees for from the standpoint of the corporate elite and their governmental and military hirelings? — provides a nice public relations opportunity and also underscores that the actual crime was the releasing of the photos and not the torture itself. At any rate, the U.S. corporate media quickly tired of torture and abuse photos; intra-media competition forced torture into the news temporarily, but there soon was a tacit understanding that we had seen enough of these photos.

Punishing the enlisted personnel who carried out their orders rather effectively — and what, after all, are enlistees for from the standpoint of the corporate elite and their governmental and military hirelings? — provides a nice public relations opportunity and also underscores that the actual crime was the releasing of the photos and not the torture itself. At any rate, the U.S. corporate media quickly tired of torture and abuse photos; intra-media competition forced torture into the news temporarily, but there soon was a tacit understanding that we had seen enough of these photos.

But however ubiquitous photography is, it has its limits. Humans see what they wish to see, which Susan Sontag amply demonstrated in On Photography, although she demonstrated that principle more than she intended. Ms. Sontag’s book is a collection of six essays written for The New York Review of Books during the 1970s, as the Vietnam War was winding down. The Pentagon certainly has taken a lesson from that war, taking strong measures to censor photography and videography today. But the military, and the economic interests for which it serves, is more than capable of using photography for its own purposes. This is not new, Ms. Sontag notes:

“The photographs Mathew Brady and his colleagues took of the horrors of the battlefields did not make people any less keen to go on with the Civil War. The photographs of ill-clad, skeletal prisoners held at Andersonville inflamed Northern opinion — against the South. … Photographs cannot create a moral position, but they can reinforce one — and can help build a nascent one.”1

Ms. Sontag also noted the propaganda value that a photo can have, although a photo can be so iconographic that it transcends it political use value.

“The photograph that the Bolivian authorities transmitted to the world press in October 1967 of Che Guevara’s body, laid out in a stable on a stretcher on top of a cement trough, surrounded by a Bolivian colonel, a U.S. intelligence agent, and several journalists and soldiers, not only summed up the bitter realities of contemporary Latin American history but had some inadvertent resemblances, as John Berger has pointed out, to Mantagna’s ‘The Dead Christ’ and Rembrandt’s ‘The Anatomy Lesson of Professor Tulp.’ What is compelling about the photograph partly derives from what it shares, as a composition, with these paintings. Indeed, the very extent to which that photograph is unforgettable indicates its potential for being depoliticized, for becoming a tireless image.”2

Her argument here is that photography unnaturally beautifies what it captures, even “the small Jewish boy photographed in 1943 during a roundup in the Warsaw ghetto” with “arms raised in terror.”3 Ms. Sontag’s lament (critique would be too strong a word) is in contradiction to her themes elsewhere in the essays when focused on cultural analyses. This contradiction is most sharply in focus in her unwarranted criticisms of Diane Arbus, which frankly say much more about Ms. Sontag herself than Ms. Arbus. Ms. Sontag, with an air of disapproval, claimed that Ms. Arbus’ work

“lined up assorted monsters and borderline cases — most of them ugly; wearing grotesque or unflattering clothing; in dismal or barren surroundings. Arbus’s work does not invite viewers to identify with the pariahs and miserable-looking people she photographed. Humanity is not ‘one.’”4

A “freak” is in the mind of the viewer

To be sure, Diane Arbus’ work took a dark turn in her final works, a collection grouped as “Untitled, 1970-71” in the retrospective organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art that showed at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in spring 2005. But her mental health must have been a factor during this period; she committed suicide in 1971. Her skill, fully put to use prior to her final series, was to bring out the humanity in her subjects and to coax out their personality. Ms. Sontag’s repeated reproaches to Ms. Arbus for showing “victims” who are “pathetic,” “pitiable” and “repulsive,” in which “everybody looks the same,” only paint Ms. Sontag as uncomfortable with ordinary people even as her political sympathies were clearly with them. “Anybody Arbus photographed was a freak,”5 citing, as one of several examples, a boy waiting to march in a pro-war march wearing a “Bomb Hanoi” button.

But why is this earnest young man a “freak”? The picture is of a naïve, fresh-scrubbed boy, rather typical of the 1960s, and shows the young man as he is. His politics, undoubtedly the product of teaching from a conservative family, are horrible. We can recoil at the ignorance of wishing to bomb people for the crime of resisting an invasion; we can be amused at the absurdness of the sight (we can easily feel both), but this falls far short of reaching the status of “freak,” especially as plenty of United Statesians, sadly, supported the Vietnam War.

One picture in the Arbus retrospective that particularly stands out is “The 1938 Debutante of the Year at Home, Boston, 1966,” a picture of an extremely privileged woman well into the transition from middle age to seniority smoking in her bed. Every pore of this woman exudes privilege, captured in astonishing clarity by Ms. Arbus, a perhaps unequaled master of technique. This woman, like most of those whom Ms. Arbus photographed, was said to have loved the photo. Why not? It certainly captured this woman brilliantly. This woman most assuredly would not have considered herself a “freak.”

One photo that Ms. Sontag did specifically mention in her catalogue of horror is the “human pincushion” of New Jersey, a middle-aged man who, while demonstrating his specialty, nonetheless is very proud. The privileged once-debutante and the circus performer are both far removed from the life experiences of most people, but both, as are most of Ms. Arbus’ subjects, clearly are comfortable with themselves and thus in front of the camera. That they are “freaks” because they are different, or simply comfortable with their differences, is a terribly elitist attitude, and a misreading of Ms. Arbus’ work.

On the larger terrain of consumerist culture and national privilege, Ms. Sontag was on firmer ground, although her dismissal of Surrealism is jarring. She wrote:

“Surrealism is the art of generalizing the grotesque and then discovering nuances (and charms) in that. No activity is better equipped to exercise the Surrealist way of looking than photography, and eventually we look at all photographs surrealistically. People are ransacking their attics and the archives of the city and state historical societies for old photographs. … The Surrealist strategy, which promised a new and exciting vantage point for the radical criticism of modern culture, has devolved into an easy irony that democratizes all evidence, that equates its scatter of evidence with history. Surrealism can only deliver a reactionary judgment; can make out of history only an accumulation of oddities; a joke; a death trip.”6

Reactionary? Pressing ahead with this ultra-left phrasemongering, Ms. Sontag wrote:

“Surrealists, who aspire to be cultural radicals, even revolutionaries, have often been under the well-intentioned illusion that they could be, indeed should be, Marxists. But Surrealist aestheticism is too suffused with irony to be compatible with the twentieth century’s most seductive form of moralism. … Photographers, operating within the terms of the Surrealist sensibility, suggest the vanity of even trying to understand the world and instead propose that we collect it.”7

Photography as a privilege

Susan Sontag’s argument was part of her larger point that the ubiquity of photography is a function of the privilege of capitalist nations and that a culture based on consumerism necessarily produces photographic detritus as it does other consumer products. True enough. But consumer culture, none more so than the U.S. variety, is based on the reduction of freedom to the free choosing of products and the active trampling or co-optation of any artistic expression that does not extol consumerism, while Surrealism arose as artistic expressions in opposition to mechanized, mercantile society.

This line of attack is at least consistent with Ms. Sontag’s attack on Ms. Arbus, but is even more off the mark; the combination of squeamish cultural conservatism and “more revolutionary than thou” psuedo-radicalism makes for a creaky Stalinist muddle. Ms. Sontag had brilliant observations to make; it is difficult to understand these sorts of sojourns that only detract from her larger points.

Ms. Sontag began to develop her central themes in the opening pages, displaying the vast knowledge of photographic history that she was known for. Sontag posited that taking vacation photos, for many people, is a way of ameliorating feelings of guilt for not working and that travel is reduced to becoming a strategy for accumulating photographs.

“The method especially appeals to people handicapped by a ruthless work ethic — Germans, Japanese, and Americans. Using a camera appeases the anxiety which the work-driven feel about not working when they are on vacation and are supposed to be having fun.”8

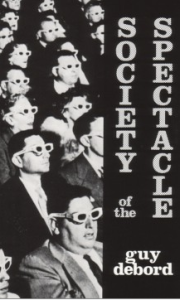

Of course, that was written before the rise of video recorders, which frequently replace the camera. This sense has only escalated with the notion that something did not happen if it wasn’t on television, and is a natural outgrowth of a hyper-consumerist society—the “society of the spectacle,” to use Guy Debord’s famous phrase. How can United Statesians be distracted, and therefore be content to buy things as a substitute for meaningful participation in their own society, unless there is a cornucopia to catch their attention. Pictures provide a part of this distraction.

Of course, that was written before the rise of video recorders, which frequently replace the camera. This sense has only escalated with the notion that something did not happen if it wasn’t on television, and is a natural outgrowth of a hyper-consumerist society—the “society of the spectacle,” to use Guy Debord’s famous phrase. How can United Statesians be distracted, and therefore be content to buy things as a substitute for meaningful participation in their own society, unless there is a cornucopia to catch their attention. Pictures provide a part of this distraction.

Ms. Sontag took this a step further, noting that “photography is acquisition in several forms,” as a surrogate possession, a consumer’s relation to events, as an acquisition of information and furnishing knowledge independent of experience.9 But photography’s utility extends to the nation as a whole, she declared:

“A capitalist society requires a culture based on images. It needs to furnish vast amounts of entertainment in order to stimulate buying and anesthetize the injuries of class, race, and sex. And it needs to gather unlimited amounts of information, the better to exploit natural resources, increase productivity, keep order, make war, give jobs to bureaucrats. The camera’s twin capacities, to subjectify reality and to objectify it, ideally serve these needs and strengthen them.”10

Of course, the camera can point more than one way, and is a convenient tool of demonstrators and others — the police generally don’t attack when the cameras are watching. Arthur C. Clarke’s maxim that there are no evil technologies, only evil uses of technology, however much we may quibble with it, rings true in regard to the camera. If the U.S. bourgeoisie ever decide to go completely to the dark side, they will surely not want the counter-revolution to be televised. Or photographed. The ubiquity of cameras would work against them, caught in a consumerist contradiction that we, Surrealist or not, can appreciate.

1 Susan Sontag, On Photography [Picador, New York], page 17

2 ibid, pages 106-107

3 ibid, page 109

4 ibid, page 32

5 ibid, page 35

6 ibid, pages 74-75

7 ibid, pages 81-82

8 ibid, page 10

9 ibid, pages 155-156

10 ibid, page 178