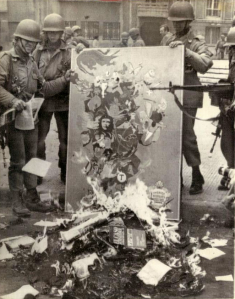

The 50th anniversary of the first 9/11 — the military coup that overthrew the democratically elected government headed by Socialist Party leader Salvador Allende — is this month. Chilean working people made enormous advances during the first year of the Allende government, formally a multiparty coalition known as Popular Unity, before Chilean capitalists, U.S. corporate interests firmly backed by the Nixon administration and right-wing elements in both countries were able to regroup and begin a heavy-handed sabotage campaign waged with increasing vehemence. In this excerpt from What Do We Need Bosses For?: Toward Economic Democracy, some of those first-year successes are recounted but the bourgeois forces are already beginning their efforts to obstruct and ultimately reverse all advancement.

For a little while more [after Salvador Allende’s government nationalized Chile’s copper industry in July 1971], Popular Unity continued to have the wind at its back. Its economic policies paid fast dividends: National unemployment dropped from six percent to four by the end of 1971, while for greater Santiago, unemployment declined from 8.3 percent to 3.8 percent, the lowest ever recorded. Importantly, most of the new jobs were in productive areas (agriculture, industry, construction) in contrast to previous years when job growth tended to be in services. Gross domestic product rose 8.5 percent for 1971, nearly double the 1960s average. Industrial growth was 12 percent, and here too this was not growth for growth’s sake — most of it was in production of basic goods such as food and clothing in contrast to past years when growth was based on durable goods such as appliances and automobiles. Wages increased 30 percent, and the labor share of income [of the Chilean economy] increased from 55 percent to 66 percent. These accomplishments were done with a significant cut in inflation. Perhaps the most basic measure of the improvement was that the poor could now afford to eat meat and buy clothes.

Storm clouds, however, began to appear on the horizon. The dramatic burst in production and living standards for 1971 had been assisted by the large amount of unused industrial capacity, the large numbers of unemployed who could be put to work, by freezing prices so that private employers couldn’t pass on the costs of wage increases to customers as had customarily been done, large inventories of goods and raw materials due to the recession that Popular Unity had inherited, and large currency reserves on which the government could draw. Further improvement would be harder to come by, in part due to the relative lag in food production.

The price of copper dropped sharply in 1971. Copper had sold as high as 84 cents per pound during the [preceding Christian Democrat] Frei administration and was still at 70 cents the first half of 1970, but would average only 49 cents for 1971. Given Chile’s heavy dependence on copper, that was a serious blow — each reduction of one cent cost the country $15 million over a year. At the same time, many products that Chile needed to import, including foodstuffs, rose in price. As 1972 began, a black market began to develop in response to these price imbalances. In addition to the rising costs of imported food (a problem difficult to tackle in the short term because Chile had long ceased to be food self-sufficient), wholesale distribution was still controlled by private capital. Instead of investing in production, that capital began to be used to buy up scarce items and re-sell them at extortionate prices.

Although much reduced for the year as a whole, inflation had begun to creep upward during the last two months of 1971; fear of renewed inflation caused the government and the national trade union federation, CUT, to agree to cap 1972 wages at the final 1971 inflation rate. The government had been printing money during 1971, a danger that would best not be continued. Individual unions resisted the wage cap despite arguments that too much of an increase would risk a resumption of inflation. And as 1972 opened, a U.S.-imposed credit blockade began, as promised by the Nixon administration. Not only was credit previously provided routinely by international lending agencies halted, routine short-term credits used to finance everyday trade were cut and even the sale of spare parts was stopped.

This was an “invisible” blockade; no official sanctions were announced. The credit blockade additionally impeded those firms that wanted to sell their products in Chile. Others that wished to do business found themselves unable to counter pressures brought to bear on them. Kennecott, one of the two major copper companies to be expropriated, filed lawsuits in Western European courts in a successful effort to halt copper sales. Chile’s chronic trade deficits, combined with the concentration of finance in New York, left the country highly vulnerable to a credit embargo, both by international lending organizations and corporate banks. This would have devastating effects, economist Richard E. Feinberg explained:

“The invisible credit blockade was the U.S.’s response to Allende’s moderate national and progressive domestic policies. The blockade reduced Chile’s capacity to import traditional consumer items, as well as the food needed by the better-off workers; Chilean industry and transport began to suffer from a lack of spare parts, and many factories had to reduce output due to a shortage of needed imported inputs, while Chile’s inability to import capital equipment undermined [Popular Unity’s] investment plans. The inevitable shortages of supply angered consumers and helped fuel inflation. The shortage of foreign exchange exacerbated social tensions.”

It was the success of Popular Unity that U.S. multinational capital feared

Although multi-national corporations compete, sometimes fiercely, with one another, they will close ranks and unite not only when the system they dominate is threatened, but when there is a sustained effort simply to contain their profits and redistribute income somewhat more fairly. Chile, a mid-sized country, hardly could constitute a threat to multi-national capital. But the example that Popular Unity had set raised alarm bells in corporate suites; if Chile succeeded in its peaceful road to socialism, other countries would surely wish to copy the example. Massive exploitation of underdeveloped countries swelled corporate coffers, and all the power they could bring to bear would be put into action, backed by the powerful governments of the global North all too willing to do their bidding.

Smaller businesses took their cues from their larger brethren.

Ariel Dorfman, who worked as a cultural and media adviser to the Popular Unity government, in his memoir Heading South, Looking North, tells of the story of “Juan,” a factory worker who was being driven out of the country into exile with him in the aftermath of the 1973 coup:

“[Allende’s] policies had created an economic boom: increased salaries and benefits led to skyrocketing consumption and that led, in turn, to a major increment in production. So, more goods sold and a better life for Juan and his co-workers, right? Not at all. The owner of the factory, opposed to the revolution, even if it did not threaten his property, had decided to sabotage production: he had stopped reordering machine parts, he had blocked distribution deals that were already in place, he refused to hire new workers and threatened to fire those who complained. He should have been making money in buckets and instead was secretly preparing bankruptcy proceedings, pulling his capital out of the industry, getting ready to flee the country. The workers had watched this class warfare patiently for months and, finally, when the owner had announced he was shutting down the whole operation, they had taken over the premises. It was the only way to save their jobs and keep producing the food that Chile needed. Allende’s government intervened in the conflict, negotiated compensation for the owner, and put the workers in control. Juan had been elected to head the council that, for a couple of years, ran that factory, and in spite of inevitable mistakes, it had been a successful venture.”

De-capitalization, removing equipment or outright closures were common reasons for the government to step in and take over enterprises; 1972 would see a steady stream of these. The example of the Yarur workers [who had taken over their textile mill in the first takeover directly accomplished by employees] had indeed quickened the tempo of the revolution. Regardless, from a macro-economic standpoint the gathering problems had to be confronted, a task made much harder by the obstinate refusal of the parliamentary opposition to approve any Popular Unity legislation.

The budget deficit had grown larger than planned due to the loss in income from softening copper prices, the increase in prices of imports, deficits in nationalized enterprises caught between rising costs and consumer-price freezes that had to be covered by the government, and the uncontrolled increase in land seizures. Revenue had to be increased. One way would be to crack down on tax evasion — the loss in 1971 just from evaded sales tax was three times the size of the deficit! The rise of the black market in 1972 would only aggravate this problem because illegal operations don’t pay taxes.

One solution to these problems would be a rationalization of the tax code, not only to reduce tax evasion, but to make the code more progressive. Popular Unity proposals to do this, however, were uniformly blocked by the Christian Democrat and National opposition. In part that was due to class interests, but also to prevent inflation from being tamed — fomenting economic chaos had become policy for the opposition parties. …

Working people weren’t experienced at management but quickly improved production

The workers who began to co-manage Chile’s growing social-property area made mistakes — having been shut out of all participation previously, how could it be otherwise? — but overall did well, both in terms of maintaining production, creating links with other enterprises and with surrounding communities, and with orienting production toward the everyday needs of Chileans.

The most comprehensive study of the social-property area was carried out by economists Juan Espinosa and Andrew Zimbalist, who performed an intensified study of 35 manufacturing enterprises that came to be part of the social-property area. The two found that in 29 of the 35 enterprises studied, productivity increased, and that the productivity improvements were sustained, even increasing over time. Those results imply that morale improved after the staff freed itself of private management, and such a conclusion is backed up in the findings that absenteeism declined, strikes were called at one-seventh the rate they had been previously, and theft and defects were reduced while more innovation was found.

Alienation from the process of production was gradually being eliminated, Espinosa and Zimbalist wrote. In their book Economic Democracy: Workers’ Participation in Chilean Industry 1970-1973 they quote a foundry production worker in an enterprise that they ranked near the median of participation levels of the 35 studied, and thus not an exceptional example. The worker said:

“We tried to break down the barriers which had been erected to divide us. We dissolved the three trade unions and formed a single one. Any executive or foreman could be submitted to the Discipline Committee. A collective bonus system was set up. In general, there was a qualitative change in human relationships. The executives and technicians attended the worker assemblies with everyone else — and their vote wasn’t worth more than that of a worker. We were all ‘workers’ with different functions — but the difference in functions didn’t define social privilege. It was the birth of a new sort of society — the reflections of our hopes and aspirations. Great perspectives opened — and for this we were ready to sacrifice ourselves — and so we did, simply because we were convinced that this would mean a better world for ourselves and our children.”

Few technicians left; in the majority of enterprises studied less than 10 percent. For all personnel, social services were greatly improved and working conditions improved. Improvements commonly done included ventilation and heating systems; construction or expansion of cafeterias; construction of day care centers; establishing first-aid clinics and purchases of ambulances, used by the surrounding community as well those working in the enterprise; initiation of cultural activities; and administrative and technical classes. Capitalists who had lost control complained that money was being wasted on these, but the money spent was less than one percent of enterprise net worth. And along with better conditions on the job was job rotation and drastic reductions in inequality; the biggest raises went to those with the lowest pay.

In the first enterprise to be seized by its workers, the Yarur textile mill (subsequently known as “Ex-Yarur”), there was a “dramatic increase” in participation, “whether measured by voting, meeting attendance, or committee membership.” At general-assembly meetings, government managers could be criticized for giving reports that were insufficiently clear and concise. At this enterprise, “the politics of deference had given way to a participatory democracy.”

Interesting as well were the product changes made — production was increasingly geared to meeting needs instead of producing for the highest possible profit, in strong contrast to how production is organized under capitalism. At Ex-Yarur, for example, the repair shop began to manufacture three-quarters of the parts previously imported and no longer available due to the U.S. blockade. The enterprise instituted the “democratization of production” to ensure popular needs, in particular serving the most deprived, in contrast to the previous régime when production for the wealthy was emphasized.

Production for people, not for the highest profit

In line with these goals, a government organization, the State Technology Institute, developed 20 affordable products to meet needs. Among these were agricultural machinery; spoons for measuring rations of powdered milk given through a government plan; inexpensive but durable furniture for housing and playgrounds; and a simple record player. “Instead of giving priority to the production of capital-intensive goods and the maximization of profit, as private companies had done in the past, the government emphasized accessibility, use value, and the geographic origin of component parts,” noted Eden Medina, a historian of science and computing, in her study of technology during the Popular Unity era.

None of this is to suggest that paradise had been reached. Problems remained, including uneven levels of participation, occasional sectarian tensions, paternalism on the part of some Communist Party leaders, lack of commitment from Christian Democratic workers and insufficient responsiveness from the state bureaucracy. The study conducted by Espinosa and Zimbalist found that the more Christian Democrats who worked in an enterprise, the more thefts and defects that were reported. Parallel to that, the more participation by the full workforce in an enterprise, the less absenteeism and thefts and the more innovation there was. Another strong pattern in the social-property area was that no layoffs occurred when economic problems arose; instead efforts were made to bolster social services.

Changes were afoot in the countryside as well. Occupations of farmland increased dramatically in frequency after Allende took office, and although the government expressed public disapproval of these wildcat actions, there were no attempts at repression, consistent with the policy that force would never be used against its base. Agricultural production increased for 1971 and 1972 (although not enough to meet demand), but production was expected to decline 15 percent for 1973 due to the bosses’ strike in October 1972, which prevented seed and fertilizer to be delivered as the Southern Hemisphere growing season began. One serious problem that had not been tackled was that food distribution remained almost entirely in private hands. State agencies bought only 14 percent of agriculture products in 1971, enabling food in capitalist hands to be diverted to the black market, causing shortages and inflation as black-market food sold at prices that were multiples of official prices.

What had not yet been set up was a system of workers’ participation in planning. Workers persistently asked to be represented on the State Development Corporation’s sectoral development committees. Industrywide meetings of workers in the textile, metallurgy, forestry and mining industries passed resolutions calling for worker participation at all levels, and the trade union federation, the CUT, began planning for a national conference that would tackle this issue. Tragically, time was running out for these initiatives.

This is an excerpt from What Do We Need Bosses For?: Toward Economic Democracy, a study of nations that have attempted to construct post-capitalist societies published by Autonomedia. Citations omitted. Sources cited in this excerpt, in the book, are Francisco Zapata, “The Chilean Labor Movement under Salvador Allende 1970-1973,” Latin American Perspectives, winter 1976; Edward Boorstein, Allende’s Chile: An Inside View; James D. Cockcroft and Jane Carolina Canning (eds.), Salvador Allende Reader: Chile’s Voice of Democracy; Richard E. Feinberg, “Dependency and the Defeat of Allende,” Latin American Perspectives, summer 1974; Ariel Dorfman, Heading South, Looking North: A Bilingual Journey; Juan G. Espinosa and Andrew S. Zimbalist, Economic Democracy: Workers’ Participation in Chilean Industry 1970-1973; Peter Winn, Weavers of Revolution: The Yarur Workers and Chile’s Road to Socialism; Eden Medina, Cybernetics Revolutionaries: Technology and Politics in Allende’s Chile; Kyle Steenland, “Rural Strategy Under Allende,” Latin American Perspectives, summer 1974