Many well-meaning people lament that our economic system is “not working.” But that isn’t true if we apply some historical context. What has capitalism wrought since its earliest days?

Capitalism is a totalizing system built on slavery, colonialism, imperialism, plunder, deeply uneven power relations and exploitation. It remains a system where “might makes right” is the “rule of law.” The “innocence” of early capitalism is a fantastical myth purporting the existence of an earlier, innocent capitalism not yet befouled by anti-social behavior and violence or by greed.

Such an innocent capitalism has never existed, and couldn’t. Horrific, state-directed violence in massive doses enabled capitalism to slowly establish itself, then methodically expand from its northwestern European beginnings. It is not for nothing that Karl Marx famously wrote, “If money … ‘comes into the world with a congenital blood-stain on one cheek,’ capital comes dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt.”

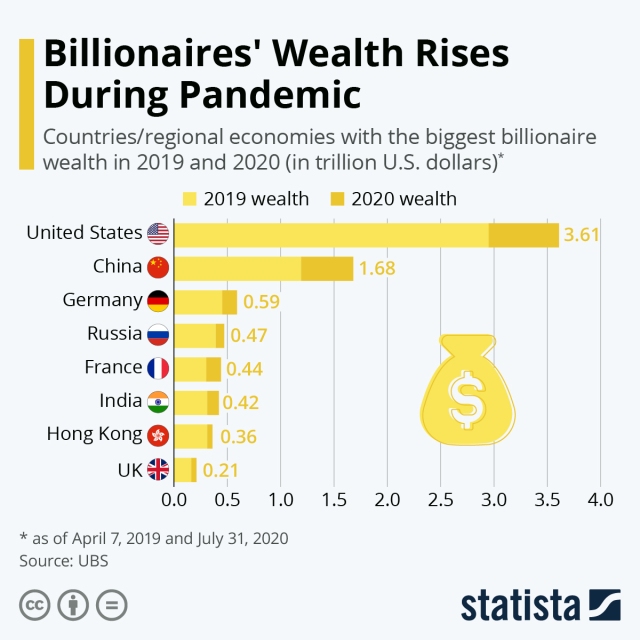

Mass movements can, and have, temporarily ameliorate the deep inequality. But always temporarily, as we can’t stay in the streets forever. Corporate globalization and the pervasive political apparatus that nurtures, sustains and expands it are ever intensifying. The holders and managers of multi-national capital accrue ever more power and wealth, which begets still more power and wealth, raising inequality to absurd levels.

The object of capitalism is for capitalists to accumulate more. A macabre race: How could any human being spend billions, tens of billions, of dollars/euros/pounds? Why would an economic system that results in such mind-boggling inequality be further rigged to increase inequality? Could we soon see the world’s first trillionaire?

This is the backdrop for the latest series of reports highlighting the madness of capitalist inequality. Let’s take a quick look while we try to put those reports in some kind of context.

Trillions for speculators, crumbs for you

At the same time that wages are stagnant, living standards are falling, inflation is hurting purchasing power and labor laws are under attack, the corporations of North America, Europe and Japan handed out an astounding US$2.75 trillion (€2.63 trillion) to shareholders in 2021. At the same time, the average pay of U.S. chief executive officers is now approaching 700 times the median pay of their employees.

That massive largesse (although even “largesse” seems inadequate) for shareholders came in two forms: $1.5 trillion in dividends paid and $1.25 trillion in stock buybacks. Simultaneous with those payouts for speculators, which have fully rebounded from the temporary declines of 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic, companies are sitting on more cash than ever. Non-financial companies in the S&P 500 Index held US$1.3 trillion in cash and cash equivalents in the third quarter of 2021, compared to $909 billion at the beginning of 2020. So, yes, they can afford to give employees a raise.

Keep this in mind when financiers scream for more austerity and bigger corporate profits, and corporate executives claim they have no choice but to cut costs by eliminating jobs, holding down wages and shipping jobs to low-wage, weak-regulation havens.

And indications so far this year show that 2022 is likely to top 2021’s records for dividends and stock buybacks. Reuters, citing Goldman Sachs, estimates that “S&P 500 companies in 2022 will spend $1 trillion buying up their own shares.” Those giant corporations spent a record $882 billion buying back their stock in 2021, and combined with the dividends handed out, S&P 500 corporations ladled out almost $1.4 trillion last year. (The S&P 500 is a stock market index that comprises 500 of the largest companies listed on U.S. stock exchanges.)

Indeed, life is good if you are a financial speculator. Or parasite, to be more blunt about it.

Financiers as whip and parasite

What is the point of a company using its profits to buy its own stock? To artificially boost how profits are reported. In short, a buyback is when a corporation buys its own stock from its shareholders at a premium to the current price. Speculators love buybacks because it means profits for them. Corporate executives love them because, with fewer shares outstanding following a buyback program, their company’s “earnings per share” number will rise for the same net income, making them look good in the eyes of the financial industry. Remaining shareholders love buybacks because the profits will now be shared among fewer shareholders.

There is a downside to this financial manipulation. You have likely already guessed who loses: Employees. They’ll have to suffer through pay freezes, work speedups and layoffs because the money shoveled into executive pay and financial industry profits has to come from somewhere. This is an unvarnished example of class warfare. A quite one-sided war.

The financial industry, and especially Wall Street, is both a whip and a parasite in relation to productive capital (producers and merchants of tangible goods and services). The financial industry is a “whip” because its institutions (firms that trade stocks, bonds, currencies, derivatives and other instruments on financial markets) bid up or drive down prices, and do so strictly according to their own short-term interests. The financial industry is also a “parasite” because its ownership of those securities enables it to skim off massive amounts of money as its share of the profits. People in the financial industry don’t make tangible products; they trade, buy and sell stocks, bonds, derivatives and other securities, continually inventing new instruments to profit off virtually every aspect of commercial activity.

In the looking-glass world of finance, the biggest drivers of this insatiable process are “shareholder activists.” These so-called “activists” aren’t activists in any customary sense. In ordinary language, an activist is someone who advocates and organizes for social advancement. But in finance-speak, an “activist” is a shareholder who has bought stock in a company for the purpose of demanding the maximum possible short-term profit, regardless of cost to others or to the company itself. “Shareholder activists” are ultra-rich speculators who are particularly aggressive in demanding that profits be handed over to them and jobs be eliminated to extract more for themselves.

Financiers and industrialists fight over the money that workers produce — profits ultimately derive from the capitalist paying the employee much less than the value of what the employee produces — but they agree they should have all of it. You and your co-workers don’t get anything more than crumbs, even though it’s the work of you and your fellow employees who create the money that is converted into gargantuan corporate profits, multi-million salaries for top executives and towering piles of money funneled into speculator pockets. The financial industry does not create money or profit. It confiscates it. That confiscation is embodied in the massive amount of stock buybacks and dividends reported above — massive not only in the raw numbers, but in the very high percentage of overall net income directed into those buybacks and dividends.

If you consume all today, what will there be tomorrow?

How high a percentage? In some years more than 100 percent! For example, in 2015 and 2016, the companies comprising the S&P 500 paid out more money in dividends and stock buybacks than the total of their net income. In 2018, following sharp increases in U.S. corporate profit levels thanks to the Trump administration’s corporate tax cuts, stock buybacks and dividends again exceeded profits. Those years are not aberrations — for the 10-year period of 2009 to 2018, such payouts totaled more than 90 percent of net income for S&P 500 corporations.

These massive payouts to financial speculators aren’t good for employees but are also not good for the long-term health of the corporations handing out the money, something frequently discussed within industry circles. For example, the Harvard Business Review, hardly hostile to business, in a January 2020 article titled “Why Stock Buybacks Are Dangerous for the Economy,” wrote:

“When companies do these buybacks, they deprive themselves of the liquidity that might help them cope when sales and profits decline in an economic downturn. … Taking on debt to finance buybacks, however, is bad management, given that no revenue-generating investments are made that can allow the company to pay off the debt. Stock buybacks made as open-market repurchases make no contribution to the productive capabilities of the firm. Indeed, these distributions to shareholders, which generally come on top of dividends, disrupt the growth dynamic that links the productivity and pay of the labor force. The results are increased income inequity, employment instability, and anemic productivity.”

The Roosevelt Institution, a U.S. think tank that although liberal is far removed from hostility to capitalist institutions, also laments the runaway nature of these massive payouts of stock buybacks and dividends. The organization noted that these payouts are a choice. (Stock buybacks were illegal before neoliberalism took hold at the dawn of the 1980s). A Roosevelt Institute paper, “Regulating Stock Buybacks: The $6.3 Trillion Question,” had this to say:

“Total spending by all publicly traded companies on stock buybacks between 2010–2019 totaled $6.3 trillion, according to their 10-K and 10-Q public filings. Shareholder payments––stock buybacks plus dividends––have on average totaled 100 percent of nonfinancial corporations’ corporate profits over the last decade. Corporate stock is largely owned by wealthy households; the top 10 percent of US households by wealth own 85 percent of corporate equity. To allow this level of buyback activity is a clear policy choice: The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has encouraged stock-price manipulation through SEC Rule 10b-18, which essentially lets companies conduct buybacks in any amount, despite purported limits, as it does not enforce its rules nor does it collect real-time data on stock buyback activity.”

With Canadian and European Union regulators lifting temporary restrictions on banks buying back stock and paying dividends in 2021, it is inevitable that we will see more of these. The European Central Bank, the anti-democratic institution that is the most powerful entity within the EU, called its lifting of restrictions “a vote of confidence in the sector’s resilience to the fallout from the coronavirus pandemic” while Canada’s “six largest banks could return a combined C$47 billion ([US]$38 billion) in cash to shareholders and still exceed regulators’ capital requirements.”

Even Forbes magazine, the self-described “capitalist tool,” admits that dividend payouts are “immense.” And this is a global phenomenon. “In 2021, dividends from UK, Europe and Australian markets grew the fastest compared with 2020, thanks to a recovery in the mining and banking sectors,” Forbes reports. Oil and gas companies are also joining the party — the seven biggest energy companies, including BP, Shell, ExxonMobil and Chevron, will spend as much as US$41 billion (€39.2 billion) in stock buybacks this year, according to the Financial Times.

No wonder regulatory officials are bullish on banks. The central banks of five of the world’s biggest economies have spent about US$10 trillion since 2020 on “quantitative easing,” the technical name for central banks intervening in financial markets by creating vast sums of money specifically to be injected into them and thereby inflating stock-market bubbles. This artificial propping up of financial markets is done through central banks buying their own government’s debt and also buying corporate bonds and mortgage-backed securities. As of February 2022, the U.S. Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, Bank of Japan, Bank of England and Bank of Canada spent a composite US$9.94 trillion (€8.76 trillion) from the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic on quantitative easing. And that is not the only program in which central banks showered banks with limitless largesse.

Do executives really work 700 times harder than you do?

Not unrelated to the massive amounts of money siphoned to financiers is the extraordinarily bloated pay of top executives, exemplified by chief executive officer pay. A report just published by the Institute for Policy Studies reveals that the average gap between chief executive officer pay and median worker pay in the U.S. is now 670-to-1 at 300 large corporations studied. Forty-nine of those companies had CEO-to-worker ratios higher than 1,000-to-1. The Institute’s study found that “CEO pay at these 300 firms increased by $2.5 million to an average of $10.6 million, while median worker pay increased by only $3,556 to an average of $23,968,” compared to one year earlier. Worse still, of the more than 100 companies at which employee pay increased below the rate of inflation (and thus a net cut in pay), two-thirds of them spent money on buying back their stock.

How extreme does this inequality get? Here are merely two examples. The Institute’s study reports, “With the $13 billion Lowes alone spent on share repurchases, the company could have given each of its 325,000 employees a $40,000 raise. Instead, its median pay fell 7.6 percent to $22,697.” A previous Institute for Policy Studies report determined that had a proposed law, the Tax Excessive CEO Pay Act, been in effect, Wal-Mart “would’ve owed an extra $1 billion in federal taxes, enough to cover the cost of 13,502 clean energy jobs for a year.” Wal-Mart’s CEO-to-worker pay ratio is more than 1,000-to-1.

Not even extraordinarily ruthless Wal-Mart, the entity most responsible for production being moved to China to take advantage of low wages, is immune from pressure imposed by financial speculators. In 2015, Wal-Mart’s stock price was bid down by speculators for the “crime” of raising its minimum wage to the lordly sum of $9 an hour. Shed no tears for the cut-throat retailer, however, as it receives billions of dollars per year in subsidies and dodges at least $1 billion in taxes annually.

Having worked our way through the latest set of awful numbers demonstrating the severity of inequality, you can be forgiven if you ask yourself “What else is new?” Inequality is an inescapable feature of capitalism. A severely anti-democratic way of organizing an economy and society. Who would intentionally design such a system? Could you imagine, in a world with egalitarian distribution with sufficient resources for all, if somebody came along and said, “I’ve got a better idea. Let’s give a few people thousands of times more than everybody else and give those lucky few overwhelming political power so that they tilt the system even more in their favor.” Such a person, in such a society, would surely be deemed insane. Yet this is widely accepted as the best system that exists or can ever exist. A system that is destroying the livability of Earth while making life more precarious for billions.

Capitalism is a system that was founded on violence, was built on violence and sustains itself on violence. That force takes many forms. Horrific, state-directed violence in massive doses enabled capitalism to slowly establish itself, then methodically expand from its northwestern European beginnings. English feudal lords began throwing peasants off their land in the 16th century, a process put in motion, in part, by continuing peasant resistance. The rise of Flemish wool manufacturing — wool had become a desirable luxury item — and a corresponding rise in the price of wool in England induced the wholesale removal of peasants from the land. Lords wanted to transform arable land into sheep meadows, and began razing peasant cottages to clear the land. Peasants could either become beggars, risking draconian punishment (up to death) for doing so, or become laborers in the new factories at pitifully low wages and enduring inhuman conditions and working hours.

A process of intensifying exploitation enabled early factory owners to accumulate capital, thereby allowing them to expand and amass fortunes at the expense of their workforces; they were also able to drive artisans out of business, forcing artisans to sell off or abandon the ownership of their means of production and become wage laborers. As the Industrial Revolution took hold, the introduction of machinery was a tool for factory owners to bring workers under control — technological innovation required fewer employees be kept on and deskilled many of the remaining workers by automating processes.

The routine use of armies, private militias and police in violently putting down any attempt by working people to defend or organize themselves, and especially harsh, often lethal, measures against strikes, helped keep capitalists in the saddle. As markets at home became saturated, the endless growth required by capitalism induced industrialists to expand to new markets, encouraged all the way by financiers, and thereby expanding the reach of capitalism and subsuming more of the world under its hegemony as processes of dispossession and resource extraction accelerated.

Violence, including through military invasions and sanctions, remains a crucial means of maintaining capitalism and of keeping the leading powers of the Global North at the top of the pyramid. Other forms of force are readily used, however. The most important use of force is via financial markets. Financial power has always been a powerful lever used by the capitalist center as the apex of the financial system has moved over the centuries from Venice to Amsterdam to London to New York, with each move to a city contained within a militarily more powerful country able to project power over larger areas. Total control of the global financial system enables the United States to impose its will on other countries, even on its Global North allies, a concentrated force used to attack challenges to capitalism and to keep itself at the system’s center.

The task of transcending this is immense, but nonetheless it is the task that must be accomplished. Greed is a human characteristic but if we go to the roots, the problem is a system that facilitates and celebrates greed. Cooperation, after all, is a human characteristic as well, one that could be facilitated and celebrated in a different world.