If capitalism is such a natural outcome of human nature, why were systematic violence and draconian laws necessary to establish it? And if greed is the primary motivation for human beings, how could the vast majority of human existence have been in hunter-gatherer societies in which cooperation was the most valuable behavior?

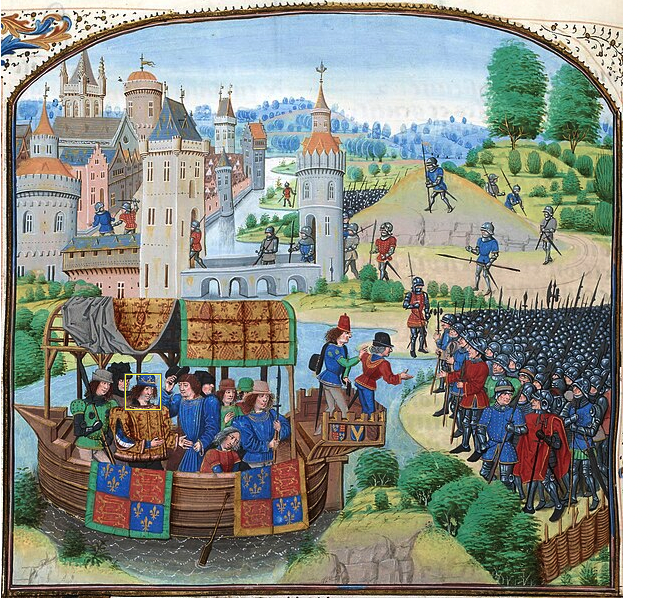

Cheerleaders for capitalism — who generate endless arguments that greed is not only good but the dominant human motivation — tend to not dwell on the origination of the system, either implying it has always been with us or that it is the “natural” result of development. Critics of capitalism, interestingly, seem much more interested in the system’s origins than are its boosters. Perhaps the bloody history of how capitalism slowly supplanted feudalism in northwest Europe, and then spread through slavery, conquest, colonialism and routine inflictions of brute force makes for a less than appealing picture. It is not for nothing that Marx wrote, “If money … ‘comes into the world with a congenital blood-stain on one cheek,’ capital comes dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt.”

A correlation of this violence applied by the elites of those times and the governments that, then as now, served their society’s elites, was that peasants and the earliest wage workers must have resisted. Indeed they did. There is a long history of resistance to capitalist offensives, and although movements, those organized and the many more that were spontaneous, were not able to bring about a more humane and equitable world, these are histories well worth knowing. A new book from Monthly Review Press, The War Against the Commons, Dispossession and Resistance in the Making of Capitalism by Ian Angus*, brings much of this history to vivid life.

Concentrating on the birthplace of capitalism, England, Mr. Angus is forthright about the violent details as they unfolded from the 15th century through to the Industrial Revolution, “focus[ing] on the first and most complete case, the centuries-long war against the agricultural commons, known as the enclosure in England and the clearances in Scotland.” At the dawn of capitalism (most commonly seen as arising in the 16th century although not firmly established until later), England and Scotland were overwhelmingly populated by farmers, much as the rest of the world. Although there was wage work, very few were dependent on it and only under capitalism did mass reliance on wage work occur.

Thus forced removal from the land, elimination of access to common lands and putting an end to the ability to live without working for others was essential for capitalism to develop, and that is the topic of War Against the Commons. In his introduction, Mr. Angus puts this forth in characteristically clear, unambiguous language:

“For wage labor to triumph, there had to be large numbers of people for whom self-provisioning was no longer an option. The transition, which began in England in the 1400s, involved the elimination not only of shared use of land, but of the common rights that allowed even the poorest people access to essential means of subsistence. The right to hunt or fish for food, to gather wood and edible plants, to glean leftover grain in the fields after harvest, to pasture a cow or two on undeveloped land — those and more common rights were erased, replaced by the exclusive right of property owners to use Earth’s wealth.”

Capitalism has only existed for a few centuries, while humans have roamed the Earth for hundreds of thousands of years. This of course is not an argument that we should go back to a hunter-gatherer existence — quite impossible given the size of the human population even if it were desirable — but simply an acknowledgment that capitalism is not “natural”; it has existed for a blink of an eye in human history.

Flipping the tragedy of the commons onto its feet

Naturally, Mr. Angus has to first clear out well-propagated misconceptions. He first shoots down the “tragedy of the commons,” a much-traveled piece of neoliberal nonsense. The originator of the concept of the “tragedy of the commons,” an ideological argument for privatization of everything, is a biology professor whose textbook argued for “control of breeding” for “genetically defective” people. Mr. Angus notes this professor “had no training in or particular knowledge of social or agricultural history” when writing his article, published in 1968. But the “thesis” was politically useful, being used to justify stealing the land of Indigenous peoples, privatizing health care and social services, and much else. What the “tragedy of the commons” “thesis” asserts is that land held and used in common will inevitably be overused and destroyed because everybody will want to use more of the common resource, such as introducing more animals on a pasture, until “common ruin” is the result.

War Against the Commons points out that no evidence was presented in this article; its thesis was simply asserted. But commons-based agriculture lasted for centuries; this success on its own disproves the thesis. Those who have actually studied how commons were used and provide actual evidence for their works demonstrate that peasants had sophisticated systems for managing commons and regulating animals.

In the early 16th century, 80 percent of English farmers grew for themselves while only the remaining 20 percent sent some of their production to markets but few of these employed labor. Differentiations were beginning to be seen, however, as complaints about enclosures began to be heard in the 1480s and the process accelerated in the 1500s. King Henry VIII’s adviser condemned enclosures, Mr. Angus writes, and a series of laws against the practice were passed, none with any effect. (The king would not seem to have taken any such advice; tens of thousands were hung during his reign as “vagabonds” or “thieves” during a time of repeated peasant uprisings.)

Mr. Angus argues that the failure of Tudor anti-enclosure legislation was due to their targeting consequences rather than causes and that judicators were local gentry who consistently sided with their colleagues. Regardless, Henry VIII conducted a massive confiscation of church lands and then sold most of it to lords, needing to raise revenue for his wars. The consolidation of large farms means there would be space for fewer small farms. Opposition to private ownership of land and greed in 16th century England was often religious, but Protestant preachers would condemn greed in one breath and in the next condemn all rebellion.

Rebellion there was, nonetheless. The dispossessed fought wage labor, which was commonly seen as “little better than slavery” and the “last resort” when all other options had been precluded. In the late 15th and into the 16th centuries, most enclosures were physical evictions, often entire villages; after 1550, landlords often negotiated with their largest tenant farmers, by now inserted into capitalist markets, to divide the commons and undeveloped lands between them. The landless and smallholders got nothing; the number of agricultural laborers with no land quadrupled from 1560 to 1620. Economic pressures were supplemented by state coercion to force the dispossessed into wage labor. A series of brutal measures were passed into law. Although there were not enough jobs for those forced into wage work, those without unemployment were classified as “vagrants” and “vagabonds” and subject to draconian punishments.

A 1547 law, for example, ordered any “vagrant” who refused an offer of work to be branded with a red-hot iron and be “literally enslaved for two years.” The new slave was subject to having iron rings put around their neck and legs and to suffer beatings. A 1563 law mandated that any man or woman up to the age of 60 could be compelled to work on any farm that would hire them, anyone who offered or accepted wages higher than those set by local employers acting as judges could be thrown in jail, and written permission was needed to leave a job on pain of whipping and imprisonment. Other laws mandated “whippings through the streets until bloody” with repeat offenders put to death. Many of those convicted were increasingly sent to the colonies as indentured servants, completely at the mercy of their New World masters.

Such were the tender mercies shown by nascent capitalists and the state increasingly oriented toward capitalists’ interests.

Might makes right as a foundation

With the simultaneous rise of the coal and textile industries, workers were needed — the draconian laws were the route to forcing people into jobs with low pay, long hours and sometimes dangerous conditions. Coal mining itself triggered more enclosures in the 16th century. Some landlords found that coal mining was more profitable for them than renting farmland, requiring dispossession of tenants, and remaining smallholders could be robbed of their land because they were prohibited from refusing access to minerals under their land. Early manifestations of current-day “property rights” where if you are big enough, might makes right.

Although much resistance consisted of spontaneous uprisings, there were organized campaigns. Two movements were the Diggers and the Levellers. The Levellers’ moniker comes from their “leveling” the hedges and stone fences landlords used to demarcate the lands they had enclosed; these organized groups repeatedly removed these demarcations. The Diggers were a collective movement founded by Gerrard Winstanley that sought to put theory into better practice. The Diggers created communes on common land, first on a hill near London. All members would receive a share of the produce in exchange for helping work the land.

Winstanley produced a program that criticized the inhumanity of the wealthy and stated that the road to freedom was through common ownership of the land. Wage labor, private ownership of land, and buying and selling land were all prohibited in Digger communities. Everyone was to contribute to the common stock and take only what was necessary; any penalties for free riders were designed to rehabilitate rather than punish. Winstanley and the Diggers saw private ownership of land as the cause of poverty and exploitation, and one of their demands was that all land should be given to those who would work it, including land confiscated from the church. They, after all, were living through the early days of agricultural capitalism with so many around them experiencing poverty and exploitation.

Remarkably, Winstanley’s concept, devised two centuries before Marx’s concept of communism as “from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs,” bore significant resemblances to the latter’s ideas, although Marx could not have known of Winstanley as the Diggers’ ideas were ruthlessly stamped out and were only re-discovered late in the 19th century. State-directed violence against Digger communes was not long in coming. Landlords were determined to eliminate the Diggers. Local magistrates, themselves landowners, indicted Diggers for trespass and unlawful assembly, and imposed fines too large to pay; mobs organized by landowners destroyed crops and homes until the communes had to be abandoned.

By the latter half of the 17th century, “large landowners and merchants won decisive control of the English state,” Mr. Angus writes. “In the 1700s, they would use that power to continue the dispossession of commoners and consolidate their absolute ownership of the land.” And as the Industrial Revolution began to develop, new rounds of enclosures were initiated, this time through laws enacted by Parliament, to strip people of their remaining abilities to be self-sufficient and not be forced into wage work with low pay and long hours of drudgery.

A class state promotes class interests

From the so-called “Glorious Revolution” of 1689 to the 1832 Great Reform Act, Britain was controlled by agrarian magnates and merchant capitalists; the state existed to benefit the wealthy. The author writes:

“The very rich ruled Parliament through their unchallenged domination of the House of Lords, their effective control of the executive, and their strong influence on the slightly less-rich members of the House of Commons. The lower House was elected, but only about 3 percent of the population (all male) could vote, and high property qualifications ensured that only the wealthy could be candidates. In E.P. Thompson’s words, ‘The British state, all eighteenth-century legislators agreed, existed to preserve the property and, incidentally, the lives and liberties, of the propertied.’ ”

More than 4,000 enclosure acts were passed by Parliament from 1730 to 1840, laws that affected a quarter of all cultivated land. Laws were heavily skewed in favor of big estates and the aristocracy. Peasants resisted, but had too much force arrayed against them. The displaced, unless they emigrated, became wage workers in the new factories. Development in England had been built on slavery, with the huge profits from slave-grown agricultural products and the slave trade itself providing capital for industrial takeoff. And many of the big estate owners were in a position to buy up land because of the profits they directly accrued from slave labor. Abolishing the slave trade was simply another move of economic beneficiary. Mr. Angus writes:

“Defenders of British imperialism like to brag that Britain outlawed the slave trade in 1807, but that’s like praising a serial killer because he eventually retired. The ban came after centuries in which British investors had grown rich as human traffickers, and it did nothing for the 700,000 Africans who remained enslaved in Britain’s Caribbean colonies. Britain’s vaunted humanitarianism is belied by the British army’s slaughter of rebellious slaves in Guyana — seventeen years after the slave trade was declared illegal.”

British parliamentarians, carrying out their class interests, were no less inclined to draconian legislation than had been their predecessors. From 1703 to 1830, 45 statutes were passed relating to banning all but elite landowners from hunting; these laws should be seen in the context of their time when small farmers and the landless needed to hunt to ensure they and their families had enough food to survive. The Black Act of 1723 saw 350 offenses made eligible for the death penalty; already, hanging, whipping and expulsion to Australia for hard labor were on the books for minor offenses. Even cutting down a tree could result in hanging.

That such draconian laws were repeatedly passed over long periods of time demonstrate that capitalism is not “natural” and indeed could only be imposed by force, War Against the Commons persuasively demonstrates. This is a book that is most useful for those already acquainted with this bloody history and wish to obtain more knowledge, including of the still largely unknown Winstanley and the Diggers movement, but also for those without this knowledge who wish to learn about the history of capitalism. The author writes in clear, understandable language without jargon, producing a work that requires no prior knowledge yet is useful for those who do have familiarity with the subject. Anyone who is interested in understanding the dynamics of capitalism, and cares to approach the subject with an open mind, will benefit.

* Ian Angus, The War Against the Commons, Dispossession and Resistance in the Making of Capitalism [Monthly Review Press, New York 2023]