It’s not true that humanity is committing suicide, as exemplified by the COP28 farce of a climate summit. The world’s industrialists and financiers are committing humanity to ecocide. More than ever, it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.

Death by capitalism. That phrase has a certain catchy feeling to it. But it’s no joke, is it? No, no joke at all.

No joke, and no vote. You didn’t get a vote on whether greenhouse gas emissions should continue at a pace to unleash catastrophically rising seas, unbearable heat, droughts, environmental destruction and an increasingly erratic climate in a cascade of cause and effect that will trigger still more climatic instability. The world’s capitalists — in particular, those who control and profit from fossil fuel corporations — have voted, did vote and will continue to vote for profits today and indifference to human and animal life tomorrow. Hurray!

The financial industry mentality has always been to squeeze every dollar out of a stone today and the hell with tomorrow. The fossil fuel industry mentality is much the same. Tomorrow increasingly looks like it will be hell. Tomorrow may not come for a few more decades, perhaps, but it does seem that tomorrow will arrive and it won’t be a pleasant time.

No more than a brief recap of the 28th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (as COP28 is formally known) is necessary. Destined to be even more of a farce than previous climate change summits given it was hosted by the oil-reliant United Arab Emirates with the chief executive officer of the UAE state oil company, Sultan Al Jaber, serving as COP28 president. Laughter may often be better than crying, but laughter just doesn’t seem right for this level of irresponsibility and contempt for humanity and the environment.

Perhaps next year’s COP29 can be scheduled for the offices of ExxonMobil? Or perhaps the world’s oil majors can bid on which will host? I do know that Baku, Azerbaijan, has been designated as the site for COP29 and that Azerbaijan is a significant oil and gas producer, even if not as big as the United Arab Emirates. But we might as well take the final step toward making these annual climate summits a complete farce. It would at least be more honest.

They delivered empty talk

The official COP28 website is quite cheery and is headlined “We United/We Acted/We Delivered.” Beyond continuing oil and gas profits, it is difficult to say what was delivered. The official final statement declares “the Parties agreed a landmark text named The UAE Consensus, that sets out an ambitious climate agenda to keep 1.5°C within reach. The UAE Consensus calls on Parties to transition away from fossil fuels to reach net zero, encourages them to submit economy-wide Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), includes a new specific target to triple renewables and double energy efficiency by 2030, and builds momentum towards a new architecture for climate finance.”

When we look at the details, we find that the “UAE Consensus” is “An unprecedented reference to transitioning away from all fossil fuels to enable the world to reach net zero by 2050” and that “economy-wide emission reduction targets” are “encouraged.” In other words, nothing concrete. What does “transition away” mean? Not much. And that countries are “encouraged” to reduce greenhouse gas emissions means that, as with past climate summits, there are no mechanisms to ensure any promises are kept. And are environmental organizations seen as relevant to any process of reducing emissions? Certainly not! Instead, finance capital will save us: Another point is “Building momentum behind the financial architecture reform agenda, recognizing the role of credit rating agencies for the first time, and calling for a scale up of concessional and grant finance.”

Banks are not going to save us. From 2015, when the Paris Climate Accord was signed, through 2022, 60 of the world’s biggest banks have invested US$4.6 trillion in fossil fuel projects. And the amount of money the controllers of finance capital are investing is growing: $742 billion was invested in the industry in 2021 alone. Four United States-based banks were the worst offenders, according to a report by seven environmental organizations, and three Canadian banks are among the top dozen in the world for financing fossil fuels. Each of these are big contributors to fracking and tar sands production. It’s not only companies like Saudi Aramco and the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company.

What was that about crying or laughing? So it’s more idle talk, the same as previous climate summits. Last year’s COP27 in Egypt established a “loss and damage” fund for Global South countries that remains voluntary and features an implementation plan that “requests” countries that have not yet done so “revisit and strengthen” their 2030 climate targets. Note that word: “requests.” Oh please consider stopping your environmental destruction if it’s not too inconvenient. That was preceded by COP26 in Glasgow failing to enact any enforcement mechanisms; COP25 in Madrid concluding with an announcement of two more years of roundtables; COP24 in Katowice, Poland, promoting coal; and COP23 in Bonn ending with a promise that people will get together and talk some more.

A vague declaration that countries will “transition away” in some unspecified and non-enforceable way is consistent with past climate summits. And what might be expected from a conference in which a record number of fossil fuel delegates were in attendance — more than 2,400 and four times more than were in attendance at COP27. For added fun, the COP28 president, Sultan Al Jaber, declared that a phaseout of fossil fuels would “take the world back into caves” and that there is “no science out there, or no scenario out there, that says that the phase-out of fossil fuel is what’s going to achieve 1.5 [degrees] C.” The OPEC cartel of oil-producing countries declared its members should “proactively reject” any reduction target aimed at fossil fuels and ExxonMobil’s chief executive officer, Darren Woods, complained that climate talks focus too much on renewable energy.

The world was not impressed

Thus it is with less than surprise that independent assessments of COP28 are less than glowing. Here is the assessment of Climate Action Tracker:

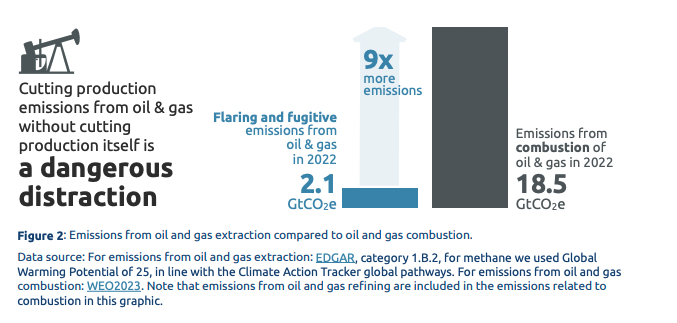

“Few of the sectoral initiatives announced during COP28 will meaningfully contribute to closing the emissions gap. Many of them lack either the ambition, clarity, coverage or accountability needed to really make a difference. We estimate that of the total emissions savings that could be achieved by the pledges, around a quarter is already included in government [nationally determined contributions], around a quarter is additional and achievable, and around half is unlikely to be achieved without further action to improve the initiatives. … The ‘Oil and Gas Decarbonisation Accelerator’ is a prime example of a greenwashing initiative by oil and gas companies. It only focuses on upstream emissions from oil and gas production — but the real change has to come from phasing out fossil fuels, where emissions are at least five times greater.”

The “Oil and Gas Decarbonisation Accelerator” is a promise by oil companies to reduce emissions that occur during the production of oil and gas, including a halt to “routine flaring” by 2030. Climate Action Tracker’s report states that “The initiative risks being a distraction that misses the woods for the trees.” That is because emissions from the combustion of oil and gas are nearly nine times greater than the emissions from oil and gas extraction. In other words, it is fossil fuels themselves that must be phased out because it is their use that is responsible for the lion’s share of greenhouse gas emissions. But the likelihood of meaningful reduction of production emissions is “negligible” because China and Russia have not signed up to this initiative, while Canada, Norway and the United States “are way behind in meeting their 2030 emissions reduction targets,” and would need to fulfill this promise to make progress on overall reduction pledges.

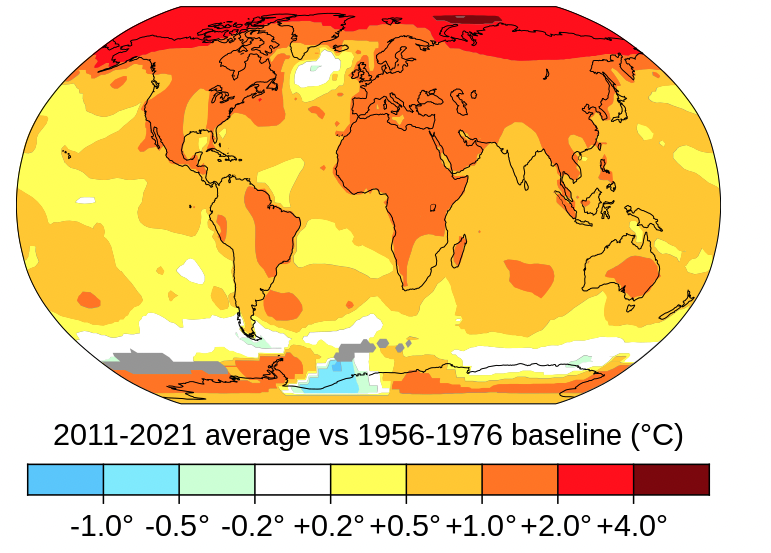

Overall, the world is nowhere near successfully limiting global warming to the Paris Climate Summit goal of holding global warming to 1.5 degrees C. above the pre-industrial level. Even if all current pledges were to be met, a temperature increase of 2.1 degrees by 2100 can be expected, and if current business as usual continues, the world is looking at an increase of 2.7 degrees by the end of the century. And of course if there is no serious mitigation, temperature rises will not stop in 2100.

None of this has gone unnoticed. More than 300 civil society organizations signed a letter calling for a phaseout of fossil fuels as part of an equitable global energy transition. Declaring that “The only way to achieve the ambition of the Paris Agreement is to substantially reduce the extraction and consumption of fossil fuels, starting now,” the letter states:

“COP28 must adopt a comprehensive energy transformation package with legal force – including a full, fast, fair, and funded fossil fuel phaseout, renewable energy and energy efficiency targets, real protections for people and nature, and massively scaled up public funding on fair terms. … By refusing to commit to address the emissions from oil and gas being burned and to end fossil fuel expansion, the proposed ‘Global Decarbonization Accelerator’ would serve as a smokescreen to hide the reality that we need to phase out oil, gas, and coal.”

Will there be enough to eat?

The world’s food supply is at stake in this environmental crisis as well. Representatives of small farmers, such as La Via Campesina, were drowned out by lobbyists for Big Agriculture. Large U.S.-based meat and dairy companies have “spent millions campaigning against climate action and sowing doubt about the links between animal agriculture and climate change,” according to New York University research. Speaking with Inside Climate News, Oliver Lazarus, one of the study’s three authors, said, “These companies are some of the world’s biggest contributors to climate change.” A report in DeSmog notes, “While big meat and dairy corporations have spent millions lobbying against climate action, smallholder farmers are disproportionately victims of the climate crisis.” The DeSmog report added, “While small farms feed most people in low- and middle-income nations, they are responsible for only a fraction of global farming emissions. Helping smallholders to adapt and respond to climate change is fundamental for climate justice.”

The world’s capitalist food system brings us inflation, hunger and waste — more than one-third of the world’s population did not have access to adequate food in 2020, according to a United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization report.

Is it really necessary to restate the case? Another UN study, Emissions Gap Report 2022: The Closing Window, states that climate policies currently in place “point to a 2.8°C temperature rise by the end of the century.” The report adds, “only an urgent system-wide transformation can deliver the enormous cuts needed to limit greenhouse gas emissions by 2030: 45 per cent compared with projections based on policies currently in place to get on track to 1.5°C and 30 per cent for 2°C.”

As a final piling on, there is the Global Tipping Points report issued by a consortium of scientists and issued by Exeter University in Britain. “Harmful tipping points in the natural world pose some of the gravest threats faced by humanity,” the report says. “Their triggering will severely damage our planet’s life-support systems and threaten the stability of our societies.” Five tipping points already at risk of breaching are the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets, warm-water coral reefs, North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre circulation and permafrost regions. These would have catastrophic consequences:

“For example, the collapse of the Atlantic Ocean’s great overturning circulation combined with global warming could cause half of the global area for growing wheat and maize to be lost. Five major tipping points are already at risk of being crossed due to warming right now and three more are threatened in the 2030s as the world exceeds 1.5°C global warming. The full damage caused by negative tipping points will be far greater than their initial impact. The effects will cascade through globalised social and economic systems, and could exceed the ability of some countries to adapt. Negative tipping points show that the threat posed by the climate and ecological crisis is far more severe than is commonly understood and is of a magnitude never before faced by humanity.”

Nonetheless, the capitalist system’s industrialists and financiers, and the governments that cater to them and bend to their will, would like nothing more than to continue business as usual. That will soon be impossible. Once again, our descendants — living in a world of flooded cities, food shortages, resource depletion, mass species die-offs, unprecedented human migration and large numbers of people dying should business as usual continue — are not likely to believe that their ruined world would be a fair tradeoff for a handful of industrialists and financiers of the past getting obscenely rich. We live in a global economic system under which it is profitable for a handful of powerful people to profit from the destruction of the environment, and this behavior is richly rewarded. The end of capitalism is precisely what must be envisioned. Organize like your life depends on it, because it does.