Who decided we should give all our money to landlords? Did you vote for that? I didn’t. You didn’t, either. And if you have thoughts of leaving renting behind to buy, the costs of mortgages are, not surprisingly, rising dramatically as well.

As far as I know, no landlord has been recorded as holding a literal gun to the head of tenants to sign a lease. But then there is no need for them to do so, as “market forces” do the work for them. At bottom, the problem is that housing is a capitalist market commodity. As long as housing remains a commodity, housing costs will continue to become ever more unaffordable. To put this in other words: As long as housing is not a human right, but instead something that has to be competed for and owned by a small number of people, the holders of the good (housing) will take advantage and jack up prices as high as possible.

This is simply “market forces” at work. If there isn’t enough housing, and especially insufficient lower-priced housing, the owners of that commodity in short supply will raise prices. Several decades of allowing the “market” to handle the supply has led to the result of renters struggling with high rents and facing the impossibility of obtaining an affordable mortgage. Despite what judges have ruled, rents do not rise without human intervention. The “market” in housing are landlords and developers, and their interest is the maximum amount possible of profit, regardless of cost to everybody else. The magic of the market, indeed.

One new aspect of housing markets, at least in North America, is the entrance of financial speculators, a trend that appears to be gathering momentum. In both the United States and Canada, “investors” are buying up housing at an extraordinary pace, doing so to extract large short-term profits through raising rents and swift evictions. The gains of speculators are your losses — less housing is available and not only does the rent charged for these homes bought for speculation go up faster than they would have but fewer homes are available, thereby further driving up rents. Once again, Wall Street and Bay Street find a way to profit off a crisis.

Increasingly unaffordable rents as the result of decades of housing costs rising much faster than inflation or wages over decades is not limited to North America, of course. Capitalism is a global economic system, and it is therefore no surprise that the cost of housing is similarly rising around the world, perhaps most acutely in Britain but certainly not only there. Nonetheless, financial speculation has added an accelerant to North American unaffordability.

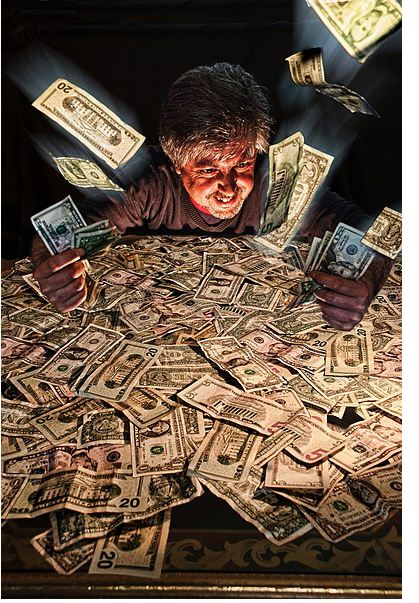

As always, Wall Street profits off everybody else’s misfortune

In the United States, speculators are gobbling up multifamily apartment buildings in places such as New York City and the San Francisco Bay Area as well as single-family homes in the Southeast, the Midwest and elsewhere. The latter seems to be drawing most of the speculative money. Investors bought one-quarter of all U.S. single-family houses that sold in 2021 with five states — Arizona, California, Georgia, Nevada and Texas — seeing nearly one-third of sales made by investors. A lack of regulation is fueling this trend. And many a political officeholder wishes to keep it that way. In Georgia, for example, a bill introduced by Republican state senators would have made it illegal for local governments to enact any restrictions against predatory behavior. Strong pushback caused the bill to die in committee but it could be resurrected. Rising rents, mass speculator buying and faster evictions are intertwined problems in places such as Atlanta, to which we will return.

By 2030, by one estimate, 40 percent of U.S. single-family rental homes may be owned by institutions. Predatory investors did not appear out of the blue, but were encouraged by federal government policy, a development not independent of the 2008 financial collapse that led to massive foreclosures and evictions. Local Initiatives Support Corporation, an advocacy group that calls itself a “bridge” between government, foundations and for-profit companies on the one hand and residents and local institutions on the other, summarizes the factors leading to the current speculation-driven market. Julia Duranti-Martínez writes:

“While predatory investors aggressively capitalized on tenant and small landlord distress to increase their market share through the pandemic, their entry into the housing market was facilitated by financial and regulatory reforms from the 1980’s-90’s, and dramatically increased in the wake of the 2008 foreclosure crisis, when investors scooped up distressed homes in hard-hit communities through bulk sales. These acquisitions are part of a long history of displacement and wealth extraction targeting low-income and BIPOC communities—particularly Black and Latinx households, who suffered higher rates of foreclosure than white homeowners and lost nearly $400 billion in collective wealth during the Great Recession—who now find themselves excluded from homeownership and paying more in rent to corporate landlords for worse quality housing.”

Although they would of course invert the moral signposts, investors themselves acknowledge that, for them, single-family homes are an “opportunity.” One institutional investor, based in Alabama, gleefully noted that scooping up single-family homes as rental properties “offers the potential for higher returns” and have become a target of institutional investors whereas these sorts of homes, prior to the 2008 financial collapse, were a “mom-and-pop asset class.” Computerization is also driving this: “[S]ophisticated real estate investors on Wall Street can partially or fully automate the process of appraising, acquiring, renovating, leasing, operating, and maintaining single-family rentals.” This report also, with a straight face, asserts that Wall Street ownership leads to “greater tenant satisfaction.” It surely does not, as we will presently see.

Seeking to unload foreclosed properties, the government-sponsored mortgage guarantors Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac began a program to encourage institutional investors to purchase these properties. This was done in 2012. Reuters quoted the then acting director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency, Edward DeMarco, as saying, “This is an important step toward increasing private investment in foreclosed properties to maximize value and stabilize communities.” Maximizing value for Wall Street it certainly has done. Reuters at the time reported that the Obama administration sought to “shore up the housing market.” Given the proclivities of the Obama administration to see neoliberal austerity and “market” solutions as the answer to all problems while giving a thin moderating veneer to otherwise right-wing concepts, it should come as no surprise that leaving renters and distressed mortgage holders to the tender mercies of Wall Street was cooked up. Par for the course for the intellectual dead end of liberalism.

U.S. government tells speculators to get to work and they do

There appears to be no letup. In March 2023, 27 percent of single-family houses sold in the U.S. were bought by investors, and that figure was virtually unchanged at 26 percent for June 2023, the latest figures I can find. The number of non-institutional purchases of single-family houses, meanwhile, declined by half from July 2020 to January 2023, according to CoreLogic data. Years of such massive purchasing by institutional investors adds up: Urban Institute researchers found that large institutional investors (those owning at least 100 single-family houses) collectively owned 574,000 homes as of June 2022, and most of these by investors owning at least 1,000 single-family rentals.

This trend is occurring in metropolitan areas around the United States, but appears concentrated in the Southeast. How does this play out? One study, published by the Housing Crisis Research Collaborative, found that private-equity and other institutional investors seek not only profits but capital gains, which are notoriously taxed at lower rates than income. “The focus on capital gains is exemplified by purchases of distressed properties in low income, historically nonwhite neighborhoods that have suffered from disinvestment, but where gentrification or real estate cycle dynamics predict medium term price increases,” the Collaborative report states. The federal Opportunity Zone program, instituted as part of the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act and described as “an uncapped, loosely targeted” policy that “provides capital gains tax shelters for investors that invest in low-income communities,” has seen “nearly all” of the funds generated by it go to real estate investment rather than business investment.

Focusing their research on Atlanta, Miami and Tampa, the Collaborative researchers found that “large corporate single family rental and rent-to-own investors purchase in highly segregated, predominantly Black and non-White Hispanic areas, while avoiding high poverty neighborhoods and areas with low levels of owner-occupied housing stock.” This included areas “hit hard by Covid-19.” As a result:

“Large corporate landlords are associated with high rates of housing instability due to frequent rental price increases and aggressive eviction practices. These firms have higher eviction rates than small landlords. Investor purchases of multifamily have been found to cause spikes in evictions-led displacement, and to accelerate displacement of Black residents at the neighborhood level.” [internal citations omitted]

This study found that large institutional owners of single-family rentals “have an established record of high hidden fees, aggressive rent increases, high eviction rates, and poor maintenance.”

Similarly, a study led by Elora Lee Raymond of Georgia Tech found a “spatially concentrated evictions rate” in Atlanta. An incredible 20 percent of all rental single-family homes received an eviction notice in 2015; in some Zip codes, 40 percent received eviction notices with more than 15 percent being evicted. Institutional investors are much more likely to evict: “We find that large corporate owners of single-family rentals, which we define as firms with more than 15 single-family rental homes in Fulton County, are 68 percent more likely than small landlords to file eviction notices even after controlling for past foreclosure status, property characteristics, tenant characteristics, and neighborhood.”

Another research report reached similar conclusions. Stateline reports that “Institutional buying in Georgia has focused on a ring of middle-class Black suburbs south of Atlanta, according to research by Brian An, an assistant professor of public policy at Georgia Tech. An said buying since 2007 was concentrated in southern Atlanta suburbs with mostly Black populations, low poverty, good schools and small affordable houses considered good starter homes.”

Heads, Wall Street wins and tails, you lose

Although the process is further along in certain cities, financialization of housing is an economic phenomenon, not a geographically specific one. Under financialization, housing is seen as an asset class used to generate financial profits, similar to stocks and bonds. Benjamin Teresa, writing for the affordable-housing publication Shelterforce, sums this up: “The financialization of housing is part of a long-term transformation of the economy, and so it has to be understood and analyzed not as a phenomenon of specific markets, such as expensive cities or supply-constrained regions, but as an emerging set of investment strategies and management practices that present real challenges to affordable housing advocates, tenants, and community development organizations.”

U.S. government policy has facilitated financialization. The 1990s reversal of the separation of commercial and investment banking put into law during the Great Depression; elimination of caps on interest rates on loans, encouraging higher-risk speculation; bailouts of banks and Wall Street that reward high-risk behavior; and the government creating a corporation to allow banks to offload their foreclosed homes instead of stabilizing tenants and owners of single homes during the Savings and Loan crisis all contributed. The Shelterforce analysis concludes:

“Financialization of housing does depend on housing scarcity, but it’s important to recognize that housing scarcity is produced in multiple ways, including by financial actors themselves. It’s not an inevitable condition financial firms are merely taking advantage of. Indeed, creating and maintaining housing scarcity through hoarding housing, gatekeeping housing, and evicting people from housing is a central preoccupation of financial investors. State-imposed austerity measures that prioritize short-term deficit reduction over functional social programs consistently reduce state support for housing, which in turn increases housing scarcity. And an attitude toward financial risk that prioritizes support to the banking and financial system above keeping people housed also produces scarcity.”

All this adds to the upward pressure on rents, already long subject to increases well above the rates of inflation or increases in wages. A May 2023 report by Moody’s Analytics — a pillar of the economic establishment hardly likely to embellish anything that would reflect badly on capitalism — found that half of U.S. renters are rent-burdened, defined as those who spend 30 percent or more of their gross income on housing. That is the highest percentage that has been recorded. A housing study conducted by Harvard University researchers also found that half of U.S. renters are rent-burdened and that the number of homeless people is at a record high. It’s not only renters who are in difficulties: When including those carrying mortgages, the Harvard researchers found that 42 million U.S. households are cost-burdened, or one-third of all U.S. households.

Being rent-burdened is bad for your health, a separate study unsurprisingly found. The study, “The impacts of rent burden and eviction on mortality in the United States, 2000–2019,” published in Social Science & Medicine, found that higher rent burdens, increases in rent burdens and evictions resulted in measurably higher levels of mortality. Evictions with judgments resulted in a 40 percent higher risk of death.

And higher rent burdens are quite common. From 1980 to 2022, rent increases in the United States averaged 8.9 percent. That has accelerated, as average U.S. rent increases were reported as 18 percent for 2021, 14 percent for 2022 and 12 percent for 2023, according to Azibo, a financial services company for the real estate industry.

Thus it comes as no shock that rents in the U.S. increased twice as fast as inflation from 1999 to 2022 while real wages were essentially unchanged during that time. If you want the numbers, rent growth in that period was 135 percent, income growth was 77 percent and inflation was 76 percent.

Canadian rents rise beyond too damn high

The housing situation in Canada is no better and may actually be worse than it is in the United States. Rents in Canada rose 4.6 percent in 2021, 12.1 percent in 2022 and 8.6 percent in 2023 from already high rates. As a result, an astounding 63 percent of Canadian renters are rent-burdened! Although inflation arose in Canada as it did in much of the world, rent far outstripped inflation: Canadian prices rose a total of 11.3 percent for the period of 2021 to 2023. Thus rents in these years rose more than twice the rate of inflation.

As it is south of the border, rents in large Canadian cities are higher than elsewhere. On a countrywide average, according to National Bank of Canada data, a Canadian needs half of a median income to be able to pay the median condo mortgage — well above the 30 percent mark at which a household is classified as cost-burdened. Condos, in turn, are less expensive than other owned housing and are often seen as “starter” homes in Canada. Overall, for all mortgages, 65 percent of a median income is necessary to pay for a median mortgage. In Vancouver, more than 100 percent of a median income would be needed. In Toronto, nearly 90 percent. How many can afford that?

Nor is any improvement on the horizon. The National Bank of Canada, in its housing affordability summary, said, “While homeownership is becoming untenable, the rental market offers little respite. Our rental affordability index has never been worse.” The bank concluded: “The outlook for the coming year is fraught with challenges. While mortgage interest rates are showing signs of waning in the face of expected rate cuts by the central bank, housing demand remains supported by unprecedented population growth. As a result, we expect some upside to prices in 2024. On the rental side, in a recently released report by the [Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation], Canada’s rental market vacancy stumbled to a record low of 1.5% which leaves little room for an improvement in rents.” The median rent for a one-bedroom apartment is an unaffordable C$2,700 in Vancouver and C$2,450 in Toronto.

Mass investor buying of homes has also reached dangerous proportions in Canada. Investors bought 30% of Canadian homes in the first quarter of 2023, up from 22 percent in 2020. Investors already owned more than one-fifth of all homes in five Canadian provinces in 2020. There is no accident here — one-third of all new properties in metropolitan Vancouver were built specifically for investment. Marc Lee, a senior economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives speaking with CBC, said, “So much of the wealth ladder in Canada has been based around real estate. I think it’s come at the detriment of quality affordable housing for the majority of folks who are renters.”

Rent controls are used on a wider scale in Canada than they are in the United States, but that hasn’t seemed to slow the dizzying rise in rents and the cost of housing in general. Ontario, for example, has instituted a province-wide cap on rent increases of 2.5 percent for 2024. That is the same cap as was promulgated for 2023. But there are catches. The conservative government of Doug Ford in 2018 enacted legislation that exempts from rent caps any home built or first occupied after November 15, 2018, nor when a tenant leaves. As a result, although tenants who remained in their rental in 2022 received an average 3 percent increase in rent, units in which there was tenant turnover saw an 18 percent increase. Preliminary calculations imply there was a 25 percent rise for units that saw tenant turnover in 2023.

Don’t wait for the “market” to correct this situation. At the same time as homelessness swells and prices rise beyond affordability, there are about 1.3 million vacant homes in Canada — about 9 percent of the country’s total. This is the fifth highest total of any Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development member country. (The United States has the most vacant homes, 15.6 million, and among all OECD countries, 10 percent of homes are vacant.)

Rents increased seven and a half times faster than wages from 2000 to 2020 in Canada. In part this is due to Canadian housing prices not taking a hit as happened in the United States in the wake of the 2008 economic collapse. But there is no downplaying the massive buying of homes, especially newer ones. And although cities such as Toronto and Vancouver draw the most attention, speculators are hungrily eyeing housing across the country. Better Dwelling, a housing news outlet, reported that investors own more than one-third of the housing and three-quarters of “recent completions” in the small northern British Columbia city of Fort St. John while snapping up more than half of new builds in another small B.C. city, Prince Rupert. “[I]nvestors are driving up home prices based strictly on the expectation home prices will always rise,” Better Dwelling said. “When this occurs, the market can become more vulnerable to an economic shock.”

“Free market” or with rent controls, European renters pay more

Across the Atlantic, rent is also too damn high. Perhaps nowhere in Europe is rent higher than in Britain. Half of all United Kingdom tenants are rent-burned with London tenants spending on average 41 percent of their income on rent. Although investors buying up homes appears to be becoming more common — investor borrowing is reported to have reached £18 billion in 2022 — it has not reached anywhere near North American levels yet. Nonetheless, British rents are up 25% since the start of the pandemic. Interest rates have been high the past couple of years, but not having a mortgage to pay seems to be no barrier to British landlords. A survey by Shelter, a tenants-rights advocate, found that two-thirds of mortgage-free landlords are raising rents anyway. It must be nice to let the money roll in while you sit with your feet on the desk: Average profits per tenant are now £800 per month.

I am unable to find any equivalent of the rent-burdened statistic for British tenants (that is, those paying at least 30 percent of their gross pay for rent) but there is no shortage of those paying too much. About one-quarter of U.K. renters are paying 40 percent or more for rent, the highest total in Europe. (Norway and Spain are next.) British rents are up 56 percent since October 2019, The Guardian reports. By comparison, real wage increase for British workers from 2019 to 2024 totals a paltry 5 percent.

One thing in common on both sides of the Atlantic is the crisis level of homeless people. Shelter reports that more than 300,000 were homeless in England at the end of 2022, nearly half of them children. That’s 14 percent more than a year earlier. So pervasive is this social problem that a separate Shelter report found that half of England’s teachers work at a school with homeless children. “For years, successive governments have failed to act on the ongoing and deepening housing emergency by failing to invest in enough social homes. The only alternative available to families is to rent privately. But rents for family homes have skyrocketed and have outpaced incomes, shutting off all options for many people,” the organization says.

Rents are high not only in England. Dublin, Paris and Oslo are reported to be the European cities with the highest rents. Despite a 3.5 percent cap on rent raises in Paris, Parisian rents rose 6.5 percent from mid-2022 to mid-2023. Reports Le Monde, “Non-compliance with rent controls is an open secret. Despite this measure, 30% of new rentals exceeded the maximum rent allowed in 2021, according to the latest available data from the Observatory of Rents in the Paris Conurbation. ‘It’s even worse for small spaces: 80% of studios don’t comply with rent control,’ said Ian Brossat, Paris’s deputy mayor for housing (Communist).” A recent city survey found that 35 percent of Paris rental properties are rented at prices higher than allowed under rent-control rules.

Rents in Dublin reached €2,102 per month in August 2022, with new tenancies 9 percent more expensive than a year earlier. The rest of Ireland appears to be catching up; although rents outside the capital are much less expensive the overall rent increase for Ireland as a whole was almost 11 percent for 2023. Rents in Oslo are reported to have risen 17 percent in a year with country-wide rents in Norway up 12 percent. Recent large increases in the price of buying a home have forced more Norwegians into the rental market, so much that a recent pause in real estate prices has not caused rent increases to slow.

Housing as a commodity rather than a human right

OK, I’ve likely provided more numbers than many readers might care to digest. So let’s ask why rents are too damn high and why they have risen much faster than inflation for so many years. As long as housing is treated as a commodity to be bought and sold by the highest bidder, housing costs will increase and we’ll remain at the mercy of landlords, who, under gentrification, decide who is allowed to stay and who will be pushed out of their homes. And as pristine markets exist only in the minds of orthodox economists, not in the real world, the wealth accrued by landlords and developers enable them to exert powerful influences on local, state and provincial political office holders, and thus push laws to their benefit. Rent controls are prohibited or not in existence in most places, especially in the United States, and often those that are in place have loopholes or weaknesses that allow landlords to raise rents anyway. And as luxury housing for the wealthy is more profitable than other housing, that is what developers will build when “markets” are left to determine what gets built.

Market forces are nothing more than the aggregate interests of the largest industrialists and financiers. Markets do not sit high in the clouds, dispassionately sorting out worthy winners and losers in some benign process of divine justice, as ideologues would have us believe. There is no magic at work here.

Neither housing, nor education, nor a clean environment are considered rights in capitalist formal democracies, and if you live in the United States, health care is not a right, either. Democracy is defined as the right to freely vote in political elections that determine little (although even this right is increasingly abrogated in the U.S.) and to choose whatever consumer product you wish to buy. Having more flavors of soda to choose from really shouldn’t be the definition of democracy or “freedom.”

That is because “freedom” is equated with individualism, a specific form of individualism that is shorn of responsibility. Those who have the most — obtained at the expense of those with far less — have no responsibility to the society that enabled them to amass such wealth. Imposing harsher working conditions is another aspect of this individualistic “freedom,” but freedom for who? “Freedom” for industrialists and financiers is freedom to rule over, control and exploit others; “justice” is the unfettered ability to enjoy this freedom, a justice reflected in legal structures. Working people are “free” to compete in a race to the bottom set up by capitalists.

Even in the United States, rent control has been used successfully in the past. In parallel with price controls on consumer goods and government guidance of the economy during World War II, the federal government established caps on rent to prevent profiteering that the government deemed a threat to civilian morale. After the war, when federal government controls were ended, rent control was devolved to state governments; not surprisingly denunciations of rent control went hand-in-hand with the anti-communist scare mongering that was quickly fanned to dampen political dissent. A brief wave of new rent-control measures was overturned in the 1980s, when Reaganism was instituted; this neoliberal turn was intended to restore corporate profits at the expense of working people. As to this latest turn, Oksana Mironova, writing in Portside, said:

“The anti-rent control push was part and parcel of a revanchist political turn that championed deregulation, austerity, and carceral solutions over measures that not only were of no benefit to marginalized people, but also dehumanized and actively harmed them. As the social safety net frayed, rent control became a convenient scapegoat for declining housing conditions, increased homelessness, and even increases in street crime.”

Housing reform is increasingly on the agenda, and there is no reason why such an activist upsurge can’t continue. Reforms advocated by housing activists such as much enhanced rent control laws and a massive increase in publicly funded housing would certainly be welcome, as would redirecting tax breaks to be used only for buildings that will have 100 percent affordable units. Any short-term solutions that can ameliorate the high cost of housing are welcome. Ultimately, however, unaffordable rent increases beyond inflation levels or wage growth will not be history until housing is no longer a capitalist commodity. Public intervention, not markets, is the solution. Why is housing not a human right?