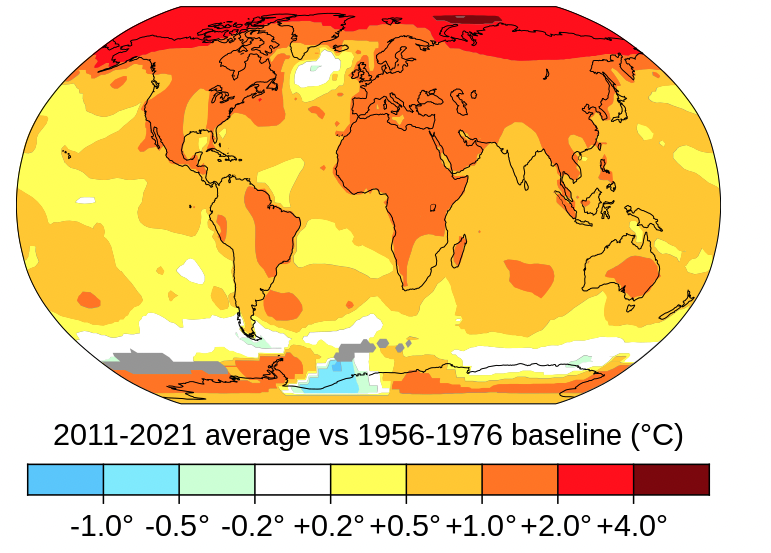

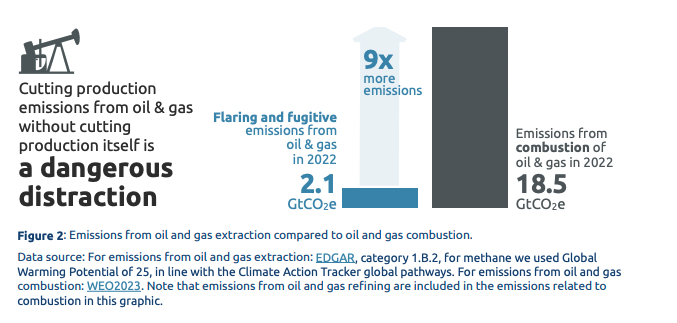

One of the two major-party candidates for the presidency of the United States has allowed an decades-long ethnic cleansing to morph into a genocide, a horror that could be stopped with one phone call; has escalated the drilling of oil and gas despite the existential threat of global warming; forced railroad workers to swallow a bad contract by breaking their strike; and spent his Senate career as an errand boy for banks. And that’s the lesser evil!

Joe Biden really is the lesser evil in this dismal race for the White House, and that such an office holder is easily not the worst candidate is surely sufficient to illustrate the decline of the world’s still extraordinarily dangerous superpower. Out of more than 300 million people, this is the best the country can do? Given the quite understandable reluctance (to put it mildly) for the types of folks who are reading these words to contemplate voting either for President Biden or Donald Trump, what do we do when the lesser evil is so evil that he has the sobriquet “Genocide” attached to his name?

At the top of the list is recognizing the limitations of voting and concentrating on organizing. There is no vote that is going to fix a hopelessly archaic voting system, a system that simply reflects the state of U.S. politics. The Democratic Party is not going to save us, no matter how fervently liberals wish to believe. Even if President Biden could somehow be magically replaced by a true progressive dedicated to putting an end to corporate control of U.S. society and all the many social, political and environmental ills that flow from that, not much would change. One person can’t be a savior and if one person could at least do something tangible to ameliorate our conditions, the Democratic Party apparatus itself would stop it. Remember the 2016 campaign — the mere presence of Bernie Sanders and his social democratic prescriptions that posed no threat to capitalism as it is practiced in the United States sent Democratic leaders into fits of frothing panic as they did everything they could to tip the scales in favor of their corporate candidate despite that candidate’s unpopularity. That candidate, Hillary Clinton, Wall Street’s choice, even intimated that she might prefer Trump in the White House than Senator Sanders.

But simply waiving off the Democrats as a party of capitalists (although true) doesn’t explain anything. We need to be more concrete. Beyond the obvious observation (again, quite true) that money talks and those with a lot of money get to do the talking, why is the Biden campaign — and Democratic Party political office candidates in general — unable to conceive of any campaign strategy other than chasing dissident Republicans and those centrists not already committed to the party? Why are even the modest goals of their own liberal base too “radical” for them? Three factors immediately come to mind: 1) A fear of the party’s progressive wing and even more those to the left of the party; 2) a lack of imagination due to being imprisoned by ideology; and 3) the internal logic of a winner-take-all political system designed by 18th century aristocrats to keep themselves in power.

Let’s take them in turn, starting with the first item. Is there any party on Earth that is more dedicated to “standing up to its base”? Is there any other party that even contemplates doing that? The Republican Party, to seek the nearest counter-example, panders to its base at all time and has even become frightened of its own base, thus the pathetic groveling at the feet of Trump that has become a standard operating procedure. Independent thinking? Even setting aside that independent thinking is verboten in conservative circles, doing so would draw the wrath of Trump or his followers. If you don’t believe that lockstep “thinking” is the default in right-wing milieus, ask yourself why talk radio skews so heavily to the hard right. Talk radio is about an authority who tells you what to think; recall the sad spectacle of Rush Limbaugh followers who called themselves “ditto heads” because agreeing with Limbaugh’s ignorant bloviating was the only permissible response by his reality-challenged fans.

And so it is now, with an ignorant barstool ranter, a total narcissist who sees other human beings as only tools for his service, a charlatan whose goal is to be a fascist dictator (and doesn’t bother to hide that), whose every mangled word, no matter how incoherent or free of reality, is received as a message from Olympus by his fans. The steady stream of reports that make their way into the news media noting that many Republican members of Congress have a diametrically opposed opinion of the Orange One-Man Crime Wave than the unquestioning fealty they express in public demonstrate merely that, although showering corporate benefactors is the only conceivable outcome of political activity in their limited minds, lockstep echoing of whatever line the leader decrees and making sure to never say anything that would anger or confuse the base is what is expected.

Money is what matters, not voters

In contrast, Democrats have no trouble at all not simply “challenging” their base but regularly launching outright attacks on their base. Both of the first two items above come into play here. In large part Democratic officials’ disdain for their voters derives from their need to raise gigantic sums of money to run campaigns, money at such a scale that it can only be raised by begging the wealthiest capitalists and the biggest corporations. Passing legislation that the party’s base would actually like to see, however tepid and failing to get at root causes, would anger their corporate benefactors. That much is obvious and as the piles of money poured into congressional and presidential campaigns reaches absurd heights, Democratic needs to placate their donors’ wishes only grows more acute.

That money talks, however, isn’t the full picture. The surrender of Democrats to neoliberal austerity, corporate control of the levers of political power and the endless erosion of working peoples’ ability to defend themselves and our working conditions, can’t be grasped without understanding the intellectual dead end of liberalism. (To be fair, this is hardly unique to U.S. Democrats; Canadian Liberals, British Labourites and European social democrats all travel the same road.) In parallel with European social democracy, North American liberalism is trapped by a fervent desire to stabilize an unstable capitalist system. The political and intellectual leaders of liberalism believe they can discover the magic reforms that will make it all work again. They do have criticisms, even if they are afraid of saying them too loud, but are hamstrung by their belief in the capitalist system, which means, today, a belief in neoliberalism and austerity, no matter what nice speeches they may make.

Those who are conflicted between their belief in something and their acknowledgment that the something needs reform, and are unable to articulate a reform, won’t and can’t stand for anything concrete, and ultimately will capitulate. When that something can’t be fundamentally changed through reforms, what reforms are made are ultimately taken back, and society’s dominant ideas are of those who can promote the hardest line thanks to the power their wealth gives them, it is no surprise that the so-called reformers are unable to articulate any alternative. With no clear ideas to fall back on, they meekly bleat “me, too” when the world’s industrialists and financiers, acting through their corporations, think tanks and the “market,” pronounce their verdict on what is to be done. As always, the capitalist “market” is nothing more than the aggregate interests of the biggest industrialists and financiers.

There is nowhere for Democrats to go other than in circles, hoping fruitlessly that some tepid reform that does nothing other than tweak a system that works against the overwhelming majority will be enough to induce another round of votes for them while not angering their corporate benefactors. The party has descended from the “graveyard of social movements” to more actively opposing movements rather than merely coopting them. Lesser evilism tends to head in a single direction. And what of the third factor from above, the internal logic of a winner-take-all political system? Simply put, a system as closed as that of the U.S. has no room for more than two parties.

The reason for such a constricted choice in the U.S. does not lie in its constitution (which makes no mention of parties), nor even in the iron-gripped dominance of its large corporations (although the Republican/Democratic split tends to replicate the industrialist/financier rivalry among capitalists). Unlike parliamentary systems that use either proportional representation to better reflect the spectrum of political opinion or use multiple-seat districts where more than one party can be seated, a legislature based on districts each with one representative is a closed system. (This includes the U.S. Senate, which, because of its staggered terms, is effectively a single-seat system in which the district is an entire state.) That these districts are heavily gerrymandered does exacerbate this closed system, but is more a symptom than a cause. When there are two entrenched parties contesting for a single seat, there is no space for a third party to emerge. The two parties are necessarily unwieldy coalitions; they must be so because they will have to contain room for people and ideas across long portions of the political spectrum. (That does not mean that all factions’ desires are incorporated into the party’s positions or are even heard).

Heads, corporate power wins; tails, you lose

Voting for a party or an individual becomes a sterile exercise in ensuring the other side doesn’t win. From the point of view of the candidates and parties, the safest strategy is one of peeling away voters from the only other viable candidate, thereby encouraging platforms to be close to that of the other viable candidate, promoting a tendency to lessen differences between the two dominant parties. If the more extreme party moves further right, this tendency means that the relatively more moderate party will also move right, keeping the gap as small as reasonably possible.

With little to distinguish the two parties, the importance of personality becomes more important, further blurring political ideas, and yet third choices are excluded because of the factors that continue to compel a vote for one of the two major-party candidates. In turn, such a system sends people to representative bodies on the basis of their personalities, encouraging those personalities to grandstand and act in an egocentric manner once they are seated. Yet even with the grandstanding, the unavoidable need to beg for dollars to be a viable candidate means keeping corporate benefactors happy. All the more do party leaders do what they can to see to it that only those already disposed to fulfill corporate wish lists get to be candidates. And in an era where wealthy industrialists and financiers are more frequently running for office themselves rather than backing someone to do their bidding, they naturally seek office through one of the two dominant parties, thereby transmitting corporate ideology back into them, while also bolstering them by linking their personal “credibility” to the parties.

The two parties do compete fiercely to win elections — they represent different groupings within the capitalist class who have a great deal of money at stake. This is a closed competition, however: They act as a cartel to keep corporate money rolling in and other parties out. Although real choice is blocked, the illusion of competition is maintained and there is enough room to allow safety valves to work when needed, such as the removal from office of an unpopular office-holder. All this makes for a remarkably stable system: One U.S. government has fallen in 230 years and on that one occasion, Richard Nixon’s vice president was seamlessly sworn in as president.

So is there any point to voting? That ultimately is a personal decision. But why not vote? It is what else we do that matters. If you spend one hour on one day a year voting and spend the rest of your year organizing, agitating and doing what you can to bring about a better world, then you have allocated your time well. That is true whether you vote for socialist or Green candidates, or whether you vote for Democrats as the lesser evil out of strategic reasons because getting a Democrat in office provides more maneuvering room for activist work than when a Republican is in office. We should be intellectually honest enough to recognize this; acknowledging that a Republican administration is worse than a Democratic one while having no illusions about Democrats should be no cause for condemnation as long as we remember that a lesser evil is still evil and social movements in the street, linking causes and aligning with people who don’t look like us or live where we do, is the only route to a better world. (I write this as someone who votes for socialists and Greens but I decline to condemn or mock others who vote otherwise for strategic reasons.)

Bring into being a better world — whether we choose to call that better world socialism or economic democracy — means putting an end to the capitalist economic system before capitalism puts an end to Earth’s ability to remain a fully habitable biosphere and completes the job of immiserating the world’s working people, the overwhelming majority of humanity. That will never be done in a voting booth. History could not be clearer on this. The hard work of organizing and building movements is the only thing that has ever made the world better and is the only thing that ever will make the world better. It will be a happy day when we can vote as we wish by voting for what we want. For now, voting for a greater evil or a somewhat lesser evil is what we are presented with, and although not voting for a lesser evil is understandable, sometimes a lesser evil means a difference between life and death; the women who will die because they can’t get an abortion and their families would surely see a difference. We ought to be able to tell the difference between a bourgeois formal democracy and the threat of outright fascism.

Even with possessing that basic knowledge, better we oppose such a miserable choice with whatever means we have at our disposal rather than offering “more revolutionary than thou” platitudes.