It would be nice to vote for somebody we like as opposed to the “lesser evil.” Two-party systems are not to be found in any law, yet variations of them are prevalent among capitalist countries.

Countries as disparate as Britain, France, Germany and Spain have two dominant national parties, although nowhere is such a system as entrenched as in the United States, where there is not the limited space for small parties found elsewhere. The reason for such a constricted choice in the U.S. does not lie in its constitution (which makes no mention of parties), nor even in the iron-gripped dominance of its large corporations (although the Republican/Democratic split tends to replicate the industrialist/financier rivalry among capitalists).

Political parties don’t exist in a vacuum. They can exist only in a political system, the two basic types of which are legislatures or parliaments based on single-seat districts and those based on proportional representation. What sort of party system a given country has is more dependent on what kind of representative body it has than on any other factor.

A legislature based on districts each with one representative is a closed system. (This includes the U.S. Senate, which, because of its staggered terms, is effectively a single-seat system in which the district is an entire state.)

When there are two entrenched parties contesting for a single seat, there is no space for a third party to emerge. The two parties are necessarily unwieldy coalitions; they must be so because they will have to contain room for people and ideas across long portions of the political spectrum. (That does not mean that all factions’ desires are incorporated into the party’s positions or are even heard).

A faction of one of these two parties might gain the upper hand at one time, especially if it is linked with an ideology promoted by an energetic bloc of capitalists, but in this instance the party will become too narrow and rigid. The other major party will inevitably benefit and eventually the factionalized party will have to loosen the grip of its dominant faction and revert to becoming a coalition if it intends to compete successfully nationally in the future. This natural elasticity provides an additional stability to a two-party system.

Personality contests instead of a focus on issues

Campaigns for elections in single-seat districts can be conducted on larger national issues or on the basis of an important local issue, but the tendency is for these elections to become contests between personalities. If the personality representing the other party is objectionable, or the other party is objectionable, then voting is reduced to the “lesser of two evils.”

Voting for a party or an individual becomes a sterile exercise in ensuring the other side doesn’t win. From the point of view of the candidates and parties, the safest strategy is one of peeling away voters from the only other viable candidate, thereby encouraging platforms to be close to that of the other viable candidate, promoting a tendency to lessen differences between the two dominant parties.

With little to distinguish the two parties, the importance of personality becomes more important, further blurring political ideas, and yet third choices are excluded because of the factors that continue to compel a vote for one of the two major-party candidates. In turn, such a system sends people to representative bodies on the basis of their personalities, encouraging those personalities to grandstand and act in an egocentric manner once they are seated.

These personalities are dependent on corporate money to get into and remain in office, and the parties they are linked to are equally dependent — the views of those with the most money are going to be heard more than other views. Corporations are the dominant institutions in advanced capitalist countries, and the accumulated wealth and power of those who lead and profit from them are able to disseminate their preferred ideologies through their influence over society’s other institutions, including educational, military and religious.

Leaders from corporate and other institutions, to be viable candidates, will seek office through one of the two dominant parties, thereby transmitting corporate ideology back into them, while also bolstering them by linking their personal “credibility” to the parties.

Compounding those tendencies, if the district boundaries can be redrawn any which way periodically, the two parties can work together so that both have “safe” seats. Elections cease to be competitive, and if you live in a district in which voters who consistently favor the other party are the majority, you are out of luck.

The two parties compete fiercely to win elections — they represent different groupings within the capitalist class who have a great deal of money at stake. This is a closed competition, however: They act as a cartel to keep corporate money rolling in and other parties out.

Although real choice is blocked, the illusion of competition is maintained and there is enough room to allow safety valves to work when needed, such as the removal from office of an unpopular office-holder. All this makes for a remarkably stable system: One U.S. government has fallen in 220 years.

More scope for parties with proportional representation

More democratic is a parliamentary system, which in almost all cases comes with some form of proportional representation. The two notable exceptions are Canada and Britain, where members of parliament are elected from single-seat districts. Both have a third national party that consistently wins seats, but nonetheless usually produce single-party governments. This system retains some of the drawbacks of a single-seat congressional system, with the additional weakness that governments in both countries often take office with less than a majority of the vote.

One common parliamentary system is a combination of some seats representing districts and some seats being elected on a proportional basis from a list either on a national basis or from large political subdivisions. This allows voters to vote for a specific candidate and for a party at the same time. There is more scope for smaller parties here, and this type of system generally features several viable parties, depending on what threshold is set for the proportional-representation seats.

There can be two dominant parties in this type of system — Germany is an example — but the major parties often must govern with a smaller party in a coalition or even in a clumsy coalition with each other (thus, Germany’s tendency to produce periodic “grand coalition” governments). Parties in a coalition government will run on separate platforms and maintain separate identities — the next coalition might feature a different lineup.

Some countries fill all parliamentary seats on the basis of proportional representation. Each party supplies a list of candidates equal to the number of available seats; the top 20 names on the list from a party that wins 20 seats gain entry. This is a system that allows minorities to be represented — if a party wins 20 percent of the vote, it earns 20 percent of the seats.

If the cutoff limit is set too high (as is the case in Turkey, where ten percent is needed), then smaller parties find it difficult to win seats and voters are incentivized to vote for a major party — thus even in this system it is possible for only two or three parties to win all seats and a party that wins less than 50 percent of the vote can nonetheless earn a majority of seats because the seats are proportioned among only the two or three parties whose vote totals are above the cutoff.

A low cutoff better represents the spectrum of opinion in a country and allows more parties to be seated. Governments of coalitions are the likely result of such a system, which encourages negotiation and compromise. A party needs to earn five percent of the vote in many of these systems, but cutoffs are set as low as two percent.

Such a system in itself doesn’t guarantee full participation by everybody; a national, ethnic or religious majority, even if that majority routinely elects several parties into parliament, can exclude a minority, as happens in, for example, Israel. The most open legislative system must be augmented by a constitution with enforceable guarantees for all.

Multiple-seat districts

Still another variant on parliamentary representation are multiple-seat districts in which districts are drawn large. Voters cast ballots for as many candidates as there are seats — a minority group in a district should be able to elect at least one of their choice to a seat. This is a system that also has room for multiple parties, and with several viable parties in the running, votes are likely to be distributed in a way that no single party can win all seats in a given district. Ireland uses such a system.

One way to ensure that multiple parties will be seated might be to limit the number of candidates any party can run to a number lower than the total number of seats — more than one party is then guaranteed to win representation.

All the systems above are based on the traditional concept of one vote for one seat. But there is no need to limit ourselves to tradition. There are voting systems that enable the casting of multiple votes. One of these is “cumulative voting.” This is a system in which each voter casts as many votes as there are seats on a legislative body. A voter can vote for as many candidates, or cast all her votes for a single candidate, as she wishes. If the voter has five votes, he can cast all five votes for a preferred candidate, or split them among as many as five candidates if he so wishes. This is a system that enables a minority to earn representation if that minority — racial, ethnic, political or some other basis — votes cohesively.

Cumulative-voting proponents argue that this method encourages the creation of coalitions, encourages attention to issues because community groups can organize around issues and elect candidates that represent those interests, and encourages high turnouts. This is a complicated system, and probably appropriate only on the local level. A few U.S. cities do use this system.

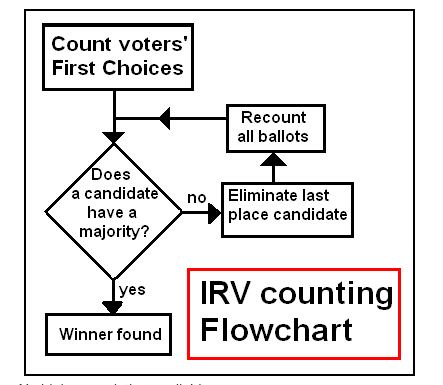

Another alternative voting system is instant runoff. Here, voters cast a ballot by voting for as many candidates as they wish, ranking each candidate. First votes are tabulated and if there is a candidate who earns a majority of votes, the winner is seated. If not, the candidate with the fewest first votes is eliminated, and the second votes on ballots that voted for the eliminated candidate are now added to the first votes on the other ballots. If there is still not a winner, there are more rounds, each time with the lowest vote-getter eliminated, until a candidate has a majority. This system works the same way for multiple-seat elections.

Another alternative voting system is instant runoff. Here, voters cast a ballot by voting for as many candidates as they wish, ranking each candidate. First votes are tabulated and if there is a candidate who earns a majority of votes, the winner is seated. If not, the candidate with the fewest first votes is eliminated, and the second votes on ballots that voted for the eliminated candidate are now added to the first votes on the other ballots. If there is still not a winner, there are more rounds, each time with the lowest vote-getter eliminated, until a candidate has a majority. This system works the same way for multiple-seat elections.

The advantage of this system is that it encourages voters to cast ballots for the candidate they truly support, as their first choice, without the need to vote only for the “lesser evil.” A voter could still choose the “lesser evil” as the second choice to block the worst choice from winning. It also ensures that there is some level of majority support for the winning candidate rather than a simple plurality. Australia uses such a system, but with an added unnecessary, undemocratic requirement mandating that all candidates be ranked (otherwise the ballot is voided). Instant runoff can be democratic only with full freedom of choice.

That any representative system truly reflect the diversity of a society in all possible ways is the important thing, and that what can be accomplished at local levels or through direct democracy be decided there.

No matter what system is used, however, a true political democracy can only exist when there is economic democracy and a measure of equality — any economic system in which a handful dominate through their immense wealth will be corrupt and undemocratic. Otherwise, we are ultimately tinkering around the edges.

You didn’t mention Australia’s “preferential voting” system. How does that fit in or compare?

Oops, you did there toward the end, sorry XD

Quite alright, Glenn, and thanks for the question. I was once very active in the Green Party of New York State in the U.S., and we handled all our internal party-post elections with preferential voting, both for specific positions and a seven-seat “coordinating committee” that represented the state branch’s highest body. The system worked very well, I thought, and tended to reflect the various factions and interests within the state party. Everybody had some representation, if they prepared well.

As I noted, this isn’t democratic if one must rank all candidates, which is a tacit vote of sorts for those who are objectionable. I am at a loss to understand why Australia has such a requirement. If there are only, say, two candidates that you can stomach, you should be able to vote for only those two candidates.